by Pavel V. Chernyshov, MD, PhD; Anastasiia Petrenko, MD, PhD; and Victoria Kopylova

by Pavel V. Chernyshov, MD, PhD; Anastasiia Petrenko, MD, PhD; and Victoria Kopylova

Dr. Chernyshov is with the Department of Dermatology and Venereology at the National Medical University in Kiev, Ukraine. Dr. Petrenko is with the Department of Dermatovenereology, Shupyk National Medical Academy of Postgraduate Education in Kiev, Ukraine. Ms. Kopylova is with Second Medical Faculty at the National Medical University in Kiev, Ukraine.

Funding: No funding was provided.

Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

Abstract: Background.Acne is a common dermatologic disease that can have a profound negative impact on a patient’s health-related quality of life (HRQoL). HRQoL correlates with acne severity in some, but not all, studies. In other words, patients with the same level of acne severity might experience different levels of impact on their HRQoL. Objective. We aimed to determine which HRQoL factors are negatively affected most in patients with acne who seek dermatologic consultation and treatment for their acne. Methods.One hundred patients with acne who sought treatment from a dermatologist (“active” patients) and 159 students with a confirmed diagnosis of acne (“passive” patients) who had not sought treatment from a dermatologist were assessed for HRQoL. To avoid differences in acne severity and possible sex differences, patients were matched according to acne severity grade (mild, moderate, or severe) and sex. All patients completed the Dermatology Quality of Life Index (DLQI) and Cardiff Acne Disability Index (CADI) questionnaires. Results.After matching, 75 active patients and 75 passive patients were selected (mean age: 22.04±4.26 years and 21.00±1.82 years, respectively; 11 male and 64 female patients in each group). Total DLQI and CADI scores were significantly higher in “active” patients. All CADI items and seven (out of 10) DLQI items were more affected by acne in the active group compared to the passive group. A significantly greater number of passive patients reported no effect on their HRQoL ,compared to the active group, and a significantly greater number of active patients reported that acne had a moderate effect on their lives, compared to the passive group. Conclusion.Our study demonstrated that the effect acne has on HRQoL is a strong predictive factor for patients seeking dermatological consultation, independent from disease severity. Embarrassment; self-consciousness; aggression and frustration; difficulties in social and leisure activities; difficulties in significant relationships with others, including partners, close friends, and/or relatives; and self-assessment of the current state of the skin were the most important predictive factors that influenced the decision for patients with acne to seek treatment from a dermatologist.

J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2018;11(7):21–25

Introduction

Acne is one of the most common dermatologic diseases1 and can have a profound negative impact on an individual’s health-related quality of life (HRQoL).2 HRQoL assessment in patients with acne is recommended by several national guidelines.3 The European Dermatology Forum’s “European Evidence-based (S3) Guideline for the Treatment of Acne—Update 2016— Short Version” recommended adopting HRQoL measures as an integral part of acne management.4 Not all patients with acne, however, seek consultation and treatment from dermatologists. For example, only 33 percent of French female adult patients with acne visited dermatologists, and 23 percent never consulted with any doctor concerning their acne. Ongoing medical treatment of acne lesions was reported only in 22 percent of patients with active acne manifestation.5 One explanation as to why fewer individuals with mild-to-moderate acne seek treatment from dermatologists compared to those with severe acne could be that the acne has less of a negative impact on their HRQoL. However, the impact that acne has on HRQoL has been correlated with acne severity in some, but not all, studies.2 In other words, patients sharing the same level of acne severity might experience different levels of negative impact on their HRQoL. In this study, we sought to define HRQoL factors that drive patients with acne to seek treatment from a dermatologist.

Materials and methods

Patients. Eligible patients were 16 years of age or older with a diagnosis of acne and absence of other manifesting skin diseases, confirmed by a dermatologist, at the time of inclusion to the study. One hundred patients with acne who sought dermatologic consultation were assessed on the factors negatively affecting their HRQoL upon admission to the clinic (“active” group). Two hundred students with self-reported acne were offered, on a voluntary basis, to receive a free dermatologic consultation and HRQoL assessment. Those who did not have acne, had manifestations of other skin diseases, or who were receiving acne treatment at the time of consultation were excluded from the study. Data from 159 patients with confirmed diagnoses of acne who had not yet sought treatment of their acne were included for further analysis (“passive” group).

Patients were matched according to acne severity grade (mild, moderate, or severe) and sex.2 Each patient in the active group was matched to a corresponding patient of the same sex and acne severity in the passive group. Ethical permission for the study was granted from the local research ethics committee. Signed consent was obtained from all patients regarding the use of collected data.

HRQoL assessment. A recent review showed that the dermatology-specific Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) and the acne-specific Cardiff Acne Disability Index (CADI) were used much more frequently than other HRQoL instruments in patients with acne.2

The DLQI consists of 10 questions, each with four possible answers. The DLQI is calculated by adding the score of each answer for a minimum possible score of 0 and maximum possible score of 30, with 0 to 1=no effect,

2 to 5=small effect, 6 to 10=moderate effect, 11 to 20=large effect, and 21 to 30=extremely large effect.6,7 Test-retest reliability, discriminant validity, internal consistency, and sensitivity to changes of the Ukrainian version of the DLQI were checked.8,9

The CADI10 is a five-item questionnaire derived from the longer Acne Disability Index.11 The CADI score is calculated by adding the score of each answer for a minimum possible score of 0 and a maximum possible score of 15, with 0=no impairment and 15=maximum impairment. The CADI can be used to assess adolescent and young adult patients.12 Test-retest reliability, discriminant and convergent validity, and over-time sensitivity of the Ukrainian version of the CADI were confirmed.13

All patients were asked to complete the DLQI and CADI questionnaires. Permission to use the DLQI and CADI questionnaires was received from Prof. A.Y. Finlay (United Kingdom). The term quimp (quality of life impairment) was recently proposed by Finlay14 and recommended by the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology Task Force on QoL and Patient-oriented Outcomes as a descriptive term used in routine clinical and research settings to indicate level of patient QoL impairment; this term was used in our study for this purpose.15

Statistical analysis. Data are presented as mean±standard deviation (SD) of the mean. Unpaired t-test with Welch correction, two-sided Fisher’s exact test, and Spearman nonparametric correlation (Spearman r) were used. The results were considered significant if p was less than 0.05.

Results

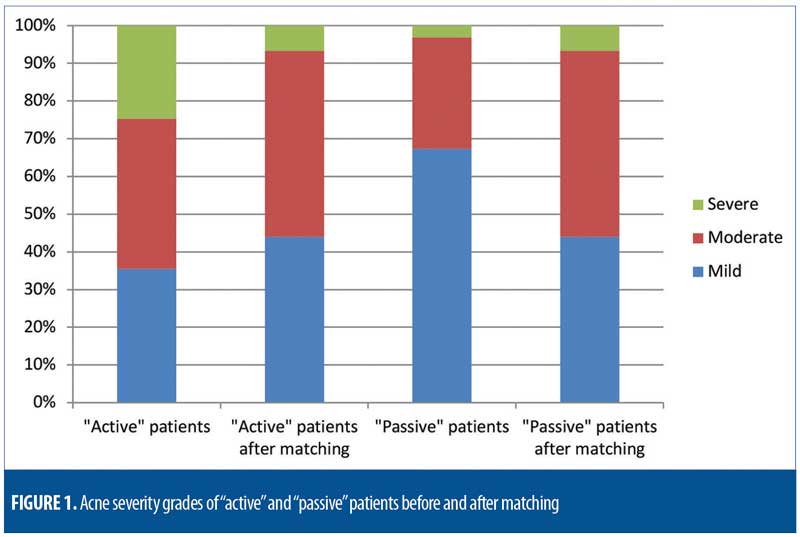

After matching the patients according to acne severity grade and sex, 75 active patients and 75 passive patients were selected for further analysis. Mean age of active patients was 22.04±4.26 years. Mean age of passive patients was 21.00±1.82 years. The difference between groups was not statistically significant. There were 11 male patients and 64 female patients in each group. Acne severity grades of the patients from both groups, after matching, were identical and are presented in Figure 1.

Both total DLQI and CADI scores were significantly higher in the active patient group. All five separate CADI items and seven out of 10 separate DLQI items indicated negative impairments of HRQoL among the active patient group (Table 1). A significantly higher number of patients in the passive group reported no HRQoL impairments. Significantly more patients in the active group indicated that acne had a moderate effect on their lives (Table 2). Total DLQI scores did not correlate with patients’ age in both groups. Only one DLQI item (“shopping or looking after home or yard”) significantly correlated with the age of patients in the active group. Neither total CADI score nor any of its separate items correlated with the age of patients from either group (Table 3).

Discussion

Before matching, the percentage of passive patients with either moderate or severe acne was in line with previous studies.16 The number of patients with either moderate or severe acne was two times higher in patients being treated by a dermatologist for their acne than in individuals with self-reported acne who were not being treated by a dermatologist. As expected, our results support the theory that acne severity is a predictive factor for seeking treatment from a dermatology clinic. However, after matching both selected dermatology-specific (DLQI) and disease-specific (CADI) HRQoL instruments, our data confirmed that quimp was higher in patients with acne who sought treatment from a dermatologist compared to patients with self-reported acne who did not seek treatment from a dermatologist, though both groups had the same level of acne severity. It is possible that some patients subjectively considered their acne symptoms to be more severe than others. Nevertheless, the results of the DLQI item on symptoms were almost identical between the active group and passive group, which suggests that complaints of acne symptoms are not predictive factors for visiting a dermatologist for acne treatment. The differences between the active group and passive group on six other DLQI items (except for the item on disease effect on treatment) were directly or indirectly related to psychological problems. In other words, differences in the items related to sports, clothing, and shopping between the active group and passive group might be explained by differences in levels of self-esteem and related psychological problems rather than by more frequent or intensive symptoms associated with acne lesions.17 Ritvo et al18 reported that nearly two out of three teenagers acknowledged that acne was a source of embarrassment. Additionally, acne-related social anxiety was negatively associated with self-esteem and intent to participate in sports/ exercise.17 All separate item scores on the brief acne-specific questionnaire (CADI) were also higher among the active patient group.

Surprisingly, acne’s effect on work or school and sexual difficulties was not associated with the decision to visit a dermatologist. Nearly all of our study participants were university students, thus acne might have had only a secondary impact on their school performance due to psychosocial problems. Some students might have had one or more jobs, but in most cases, presence of acne was not considered a barrier to getting a job. However, according to our data, getting a job might have been a problem for some patients from both active and passive groups, which makes it difficult to extrapolate the reason why patients from the passive group did not seek treatment for their acne. Perhaps they did not think treatment would have a positive effect or perhaps they thought treatment would be too expensive or have side effects.19,20

Rendon et al21 reported that approximately three-fourths of patients with acne expected to see results from their medication overnight or within 1 to 2 weeks; unmet expectations might potentially impact treatment satisfaction. One study22 investigated how much money adolescents would theoretically be willing to pay to have never had acne in their lifetime, while another study19 assessed the cost associated with a three-month course of the most effective systemic acne treatment (isotretinoin). Based on the results of both studies, it appears that adolescents would be willing to pay much less money to have never had acne in their lifetime22 than they would for three months of oral isotretinoin treatment.19 Zaghoul et a23 reported that receiving medication for free was associated with increased medication adherence. Thus, the dermatologist’s awareness of treatment costs and prescription of treatment that is within an individual patient’s financial means might facilitate improved outcomes by increasing medication procurement and adherence.19

The item on sexual difficulties was the lowest scored DLQI item by the active patient group. Acne has been reported to be associated with never having had sexual intercourse and with lower frequency of sexual intercourse,24,25 as well as with thinking that people with acne are less likely to be currently dating someone.17 Humenna et al26 recently reported the results of a survey where 16 percent of fourth-year female university students indicated they had not yet become sexually active. Taking that into consideration, we speculate that the percentage of university students who have not yet become sexually active might be higher among those with acne. It is possible that some of our study subjects who indicated “Not at all” or “Not relevant” when asked about sexual activity on the DLQI (Item: No sex-No difficulties) did so because they had not engaged in sexual activity during the one week they were given to complete the questionnaire, though they might have previously been sexually active. The DLQI item on problems with partners or close friends and the CADI item on relationships with members of the opposite sex had higher mean scores in both groups and were scored significantly higher among patients in the active group. The results indicate, however, that the presence of acne rarely caused sexual difficulties among those patients with acne who did engage in sexual activity. One woman from the active group did report a decrease in sexual desire with her partner due to mechanical irritation from her partner’s facial hair during sex, which exacerbated her facial lesions.

The effect of acne on “shopping or looking after the home or yard” was only a predictive factor for seeking treatment from a dermatologist among the older patients in the active group. This might be related to the older age associated with one who runs a household, as teen-aged and young adult patients likely would not yet have that type of responsibility, and the likelihood of independent living, forming long-term relationships, and living together with a partner increase with age.27,28

While the DLQI total scores7 showed a higher number of patients in the active group reporting a moderate effect of acne and a higher number of patients in the passive group reporting no effect of acne, six patients in the active group reported no effect of acne on their HRQoL, which suggests the HRQoL change is not the only predictive factor for seeking dermatologic consultation. Because our patients were young, their visits to the dermatologist might have been initiated by parents or other family members.

Exploring the reasons why patients in the passive group did not seek dermatologic consultation was beyond the scope of the study; however, Ritvo et al18 previously reported that less than half of parents of children with acne take the initiative to bring their children to doctors for acne treatment, and less than a third of teenagers and adults take the initiative to seek a doctor’s advice about their own acne. The most common reason for not seeking treatment was the simple belief that the skin condition was not severe enough to demand medical attention. Thus, the higher impact of acne treatment on the HRQoL of patients in the active group could be explained by the idea that patients in the passive group either did not treat their acne at all or did not go beyond basic efforts to treat outbreaks of acne18 during the one-week time frame given to complete the DLQI questionnaire.

Limitations. While the imbalance between the number of male and female patients could be considered a limitation to the study, we do not believe it decreases the reliability of our data because we had the same number of female and male patients in each group. This difference, however, could lead to underrepresentation of the male point of view. QoL differences between men and women with acne have been reported elsewhere in the literature.2

Conclusion

Our study demonstrates that the effects acne has on certain HRQoL items are strong predictive factors to seeking dermatological consultation, independently from disease severity. In our study, embarrassment; self-consciousness; aggression and frustration; problems with social and leisure activities; problems with personal relationships (dating or relationships with partners, close friends, or relatives); and self-assessed degree of severity of acne were the most significant predictive factors that influenced the decision of patients with acne to seek treatment for their acne from a dermatologist.

Our study also emphasizes the importance of educating patients with acne on how to live with and treat acne, as well as the need for the effective and timely management of acne, even for patients with less severe acne. Currently, the educational component of acne treatment is much less developed than that of atopic dermatitis or psoriasis.2 HRQoL assessment among patients with acne is still infrequent, despite there being many potential benefits from such measures.29

Acknowledgment

We thank Professor A.Y. Finlay for the permission to use the DLQI and the CADI questionnaires.

References

- Zouboulis CC. Acne and sebaceous gland function. Clin Dermatol. 2004;22:360–366.

- Chernyshov PV, Zouboulis CC, Tomas-Aragones L, et al. Quality of life measurement in acne. Position paper of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology Task Forces on quality of life and patient oriented outcomes and acne, rosacea and hidradenitis suppurativa. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:194–208.

- Chernyshov P. Dermatological quality of life instruments in children. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2013;148:277–285.

- Nast A, Dréno B, Bettoli V, et al. European evidence-based (S3) guideline for the treatment of acne—update 2016—short version. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:1261–1268.

- Poli F, Dreno B, Verschoore M. An epidemiological study of acne in female adults: results of a survey conducted in France. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15:541–545.

- Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI): a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:210–216.

- Hongbo Y, Thomas CL, Harrison MA, et al. Translating the science of quality of life into practice: what do dermatology life quality index scores mean? J Invest Dermatol. 2005;125:

659–664. - Chernyshov PV. Creation and cross-cultural adaptation of the Ukrainian versions of SKINDEX-29, SKINDEX-16 questionnaires, Psoriasis Disability Index and further validation of the Ukrainian version of the Dermatology Life Quality Index. Lik Sprava. 2009;1–2:95–98.

- Chernyshov PV. Health related quality of life in adult atopic dermatitis and psoriatic patients matched by disease severity. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2016;151:37–43.

- Motley RJ, Finlay AY. Practical use of a disability index in the routine management of acne. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1992;17:1–3.

- Motley RJ, Finlay AY. How much disability is caused by acne? Clin Exp Dermatol. 1989;14:

194–198. - Chernyshov P, de Korte J, Tomas-Aragones L, Lewis-Jones S. EADV Taskforce’s recommendations on measurement of health-related quality of life in paediatric dermatology. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:2306–2316.

- Chernyshov PV. Creation and validation of the Ukrainian version of the Cardiff Acne Disability Index. Lik Sprava. 2012;5:139–43.

- Finlay AY. Quimp: A word meaning “quality of life impairment.” Acta Derm Venereol. 2017;97:

546–547. - Chernyshov PV, Linder MD, Pustišek N, et al. QUIMP (quality of life impairment): an addition to the quality of life lexicon. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:e181–e182.

- Ghodsi SZ, Orawa H, Zouboulis CC. Prevalence, severity, and severity risk factors of acne in high school pupils: a community-based study. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:2136–2141.

- Loney T, Standage M, Lewis S. Not just ‘skin deep’: psychosocial effects of dermatological-related social anxiety in a sample of patients with acne. J Health Psychol. 2008;13:47-54.

- Ritvo E, Del Rosso JQ, Stillman MA, La Riche C. Psychosocial judgements and perceptions of adolescents with acne vulgaris: A blinded, controlled comparison of adult and peer evaluations. Biopsychosocial Medicine. 2011;5:11.

- Czilli T, Tan J, Knezevic S, Peters C. Cost of medications recommended by Canadian Acne Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Cutan Med Surg. 2016;20:542–545.

- Ayer J, Burrows N. Acne: more than skin deep. Postgrad Med J. 2006;82:500–506.

- Rendon MI, Rodriguez DA, Kawata AK, et al. Acne treatment patterns, expectations, and satisfaction among adult females of different races/ethnicities. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2015;8:231–238.

- Chen CL, Kuppermann M, Caughey AB, Zane LT. A community-based study of acne-related health preferences in adolescents. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:988–994.

- Zaghloul SS, Cunliffe WJ, Goodfield MJ. Objective assessment of compliance with treatments in acne. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:1015–1021.

- Halvorsen JA, Stern RS, Dalgard F, et al. Suicidal ideation, mental health problems, and social impairment are increased in adolescents with acne: a population-based study. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131:363–370.

- Misery L, Wolkenstein P, Amici JM, et al. Consequences of acne on stress, fatigue, sleep disorders and sexual activity: a population-based study. Acta Derm Venereol. 2015;95:485–488.

- Humenna I, Chernyshov PV. Pilot study on HPV-related cancer awareness and HPV vaccination in Ukrainian students. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:e129–e130.

- Settersten RA. A time to leave home and a time never to return? Age constraints on the living arrangements of young adults. Social Forces. 1998;76:1373–1400.

- Stone J, Berrington A, Falkingham J. The changing determinants of UK young adults’ living arrangements. Demographic Research. 2011;25:629–666.

- Finlay AY, Salek MS, Abeni D, et al. Why quality of life measurement is important in dermatology clinical practice: An expert-based opinion statement by the EADV Task Force on Quality of Life. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:424–431.