J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021;14(12 Suppl 1):S18–S23

J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021;14(12 Suppl 1):S18–S23

by Risha Bellomo, MPAS, PA-C; Matthew Brunner, MHS, PA-C; and Ella Tadjally, MPAS, PA-C

Dr. Bellomo is with Allele Medical, in Orlando, Florida. Dr Brunner is with the Dermatology & Skin Surgery Center P.C., in Stockbridge, Georgia.

FUNDING: Funded by Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, Inc.

DISCLOSURES: Ms. Bellomo is on the speaker’s bureau for Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, Inc. Mr. Brunner is on the speaker’s bureau for Dermira, Inc., EPI Health, LLC, and Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, Ltd; and is on the advisory board for AbbVie, Inc., Bristol-Myers Squibb, Castle Bioscience, Incyte Corporation, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, LEO Pharma, Sanofi Genzyme, Sol-Gel Technologies, Ltd., Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, Ltd., and UCB. Ms. Tadjally has no conflicts relevant to the content of this article.

ABSTRACT: Background. Isotretinoin is a widely used and effective drug in the treatment of severe, recalcitrant, nodular acne. However, its poor aqueous solubility limits oral bioavailability and requires administration with a high-fat, high-calorie meal (HF/HC) for optimal absorption; poor patient adherence may decrease effective dosing and treatment efficacy. Objective. This review covers the properties of the lidose isotretinoin and micronized isotretinoin formulations and their use in acne therapy. Method of Literature Search. PubMed was searched using the terms acne, isotretinoin, formulations, isotretinoin efficacy, and safety. Additional articles were searched using reference lists from the obtained results. Results. Our review discusses pathology and approved treatment options for acne; provides mechanism of action of isotretinoin; presents clinical challenges associated with isotretinoin safety; and summarizes implications in clinical practice. Newer formulations show enhanced bioavailability in both fed and fasting states. Limitations. Few published studies of real-world use of the identified formulations were available. Conclusion. Newer drug delivery technologies can simplify isotretinoin use while maximizing bioavailability and efficacy. Based on our analysis, lidose isotretinoin and micronized isotretinoin improve oral bioavailability, pharmacological bioactivity, and increase therapeutic efficacy in patients who are unwilling or unable to consistently take the medication with an HF/HC meal. Healthcare providers should consider these formulations as tools to optimize treatment based on each patient’s individual needs.

KEYWORDS: acne, acne therapy, isotretinoin, formulation

Acne vulgaris, or acne, is the most common skin condition, affecting approximately 80 to 90 percent of adolescents and 40 to 60 percent of adults.1-3 Up to 50 million Americans (~15%) suffer from acne each year regardless of sex, skin color, or ethnicity.4 Severe acne can cause considerable physical scarring and psychological damage and warrants appropriate treatment.1-3

Severe acne often requires systemic treatment.3 Oral isotretinoin is an effective systemic therapy for the treatment of severe acne, hormonal acne, and recalcitrant acne.5 Conventional isotretinoin use has challenges and limitations that have been addressed by newer formulations.6-8 This review compares currently approved and available isotretinoin formulations for acne treatment with a focus on how newer formulations simplify dosing regimens, improve bioavailability, and enhance clinical outcomes in patients with severe, recalcitrant, nodular acne. This will provide clinicians with practical information for both patient education and optimizing treatment outcomes.

The pathophysiology and current treatment of acne

Acne is a chronic inflammatory disorder with a complex multifactorial pathogenesis.9,10 Acne is characterized by excess sebum production, follicular hyperkeratinization, proliferation of Cutibacterium acnes (C. acnes, formerly Proprionibacterium acnes or P. acnes),11 and inflammatory cascades involving multiple proinflammatory cytokines and activation of immune responses3,9,10 Other contributors to and/or exacerbators of acne include genetic disposition, hormonal or neuroendocrinal dysregulation, microbial mechanisms, diet, innate and acquired immunity, stress, lifestyle, and other environmental factors.5,12 In adults, acne occurs predominantly in women—up to 85 percent of patients with adult acne are female—and is more inflammatory in nature; comedones are rare.13-15 Long-term sequelae of acne include postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH) and scarring, which are common consequences of nodulocystic acne, but are also seen in patients with chronic, uncontrolled, or even moderate acne, particularly in Skin Types III to VI.16

Acne can be alleviated and its long-term effects can be prevented by early diagnosis and timely initiation of appropriate therapy. Recommended acne treatments can be categorized as topical therapies (e.g. benzoyl peroxide, topical retinoids, topical antibiotics [erythromycin, clindamycin, minocycline], dapsone 5% gel, and azelaic acid);5,17 surface therapies (e.g. physical modalities [lasers] and photodynamic treatments), and systemic therapies (e.g. oral antibiotics, hormonal agents, combined oral contraceptive medications, and isotretinoin.)5,17 Systemic treatment is recommended for moderate-to- severe acne that is resistant to topical therapy..5 Although systemic antibiotics in conjunction with topical therapy are effective against inflammatory acne, they do not address all major contributors to acne pathogenesis.5,17

Isotretinoin: Mechanisms of action and clinical challenges

Isotretinoin (13-cis-retinoic acid) is an orally active retinoic acid derivative used for treatment of severe, refractory, nodular acne.5 Isotretinoin targets all four major contributors to acne pathogenesis.18 Treatment with isotretinoin considerably reduces sebaceous gland size and suppresses sebum production, thereby altering skin surface lipid composition. It also decreases comedogenesis, prevents C. acnes/P. acnes proliferation, and inhibits inflammation.3,18 Isotretinoin is indicated for patients with multiple nodulocystic lesions and is also used for the treatment of more moderate acne that is unresponsive to other modalities.5 Systemic isotretinoin is a clinically efficacious antiacne therapy that can achieve significant improvement and long-term remission in many patients.3,6

Overall, the safety profile of isotretinoin is favorable. Common side effects include dry skin and mucous membranes. The most significant concern is teratogenicity—exposure to isotretinoin during pregnancy is a significant risk for serious birth defects19—thus, women of child-bearing age taking isotretinoin are instructed to avoid or prevent pregnancy. Other potential or controversial adverse events associated with isotretinoin use include increased risk of depression or suicidal thoughts, anxiety, liver damage, hypertriglyceridemia, and musculoskeletal symptoms.3,5,18,19 A possible association between isotretinoin and inflammatory bowel disease has been reported, but current evidence is insufficient to support causality.20,21 Recommended laboratory monitoring may include cholesterol and triglyceride levels and standard liver function tests.5

Per American Academy of Dermatology guidelines, oral isotretinoin is a first-line choice for treatment of severe recalcitrant nodular acne.5 The recommended daily dosing regimen and treatment duration vary among different populations.22,23 In general, isotretinoin therapy should be initiated at a dose of 0.5mg/kg/day for four weeks and increased as tolerated until a cumulative dose of 120 to 150mg/kg, which is generally accepted as optimal, is achieved.3,5 Cumulative systemic exposure over the entire treatment course has been identified as a major factor in how often acne retreatment is needed.24 However, patients with moderate-to-severe acne may respond to lower dosage(s) (0.25 or 0.3–0.4mg/kg/day) and experience fewer adverse events/effects than patients receiving isotretinoin 0.5mg/kg/day.23,25

Isotretinoin is highly lipophilic and virtually insoluble in water. Although the molecule readily crosses cell membranes, the poor solubility of conventional formulations in the aqueous environment of the intestines limits absorption and thus oral bioavailability.22 Bioavailability of conventional isotretinoin can be greatly enhanced by consumption of fatty foods. Therefore, coadministration with meals is necessary to maximize bioavailability of standard isotretinoin formulations.24,26 The lipid component of food plays a vital role in the absorption of lipophilic drugs, which is the basis of the recommendations to take isotretinoin with a high-fat (50gm fat) and high-calorie (800–1000 calories) meal (HF/HC meal).22 Isotretinoin is approximately 1.5 to 2 times more bioavailable when taken with food ingested one hour prior to, concomitantly with, or one hour after dosing than when given during a complete fast.26 The gastrointestinal absorption of conventional isotretinoin decreases by 63 percent when it is taken on an empty stomach relative to administration with an HF/HC meal.24,26 As oral isotretinoin is better absorbed when taken with fatty meals, the dietary habits or patterns of teenagers and busy adults can influence patient adherence and clinical outcome. For example, more than 50 percent of teen boys and more than 66 percent of teen girls skip breakfast regularly.27 Skipping meals or avoiding high-fat foods to lose weight are also prevalent among young adults, even those who are not overweight.28 Patients ingesting conventional isotretinoin without an adequate meal or any food at all experience higher rates and earlier onset of acne relapse due to reduction in cumulative systemic exposure as high as 60 percent.24 Patient adherence with the food dependency of conventional isotretinoin for oral bioavailability is thus an important challenge in acne therapy.

New formulations of isotretinoin and optimized therapy

Several advanced technologies have been successfully employed to improve dissolution, solubility, and bioavailability of poorly soluble drugs such as isotretinoin. Innovative approaches to improve isotretinoin bioavailability are based on two features: lipid-based formulations and micronized formulation/technology.29-31 Table 1 summarizes the advantages and disadvantages of these formulations.5,7,8,26,29–31,34,40

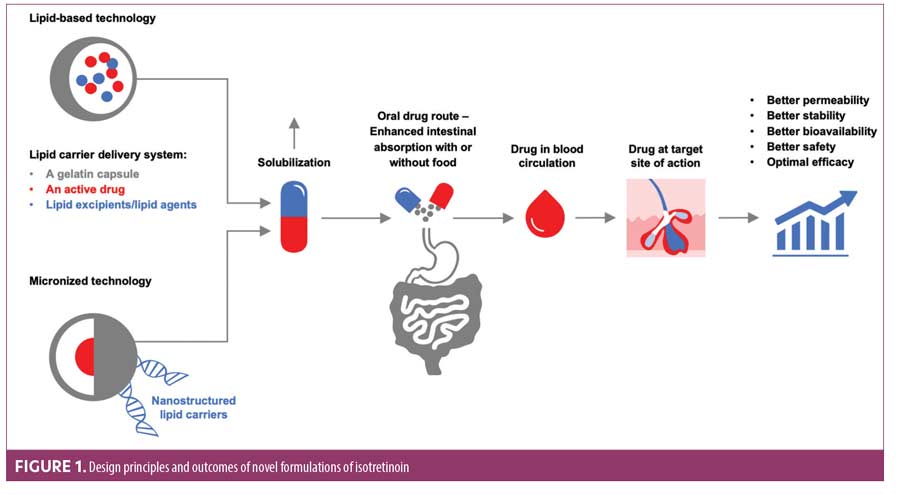

In the lidose isotretinoin formulation, isotretinoin is presolubilized in a lipid matrix through lipid encapsulation so that its absorption is less dependent on food. The encapsuled carrier delivery system,—comprising a hard gelatin capsule, an active drug, and lipid excipients—maximizes solubility of lipophilic drugs while minimizing side effects and preserving efficacy (Figure 1).29,32 Lipid-based delivery systems can be complex because of the need to select appropriate lipid components to achieve the desired solubility and additives to meet other performance objectives. The excipients employed in lipid-based formulations include lipids, surfactants, and cosolvents.32 Lipid-based delivery systems can significantly enhance intestinal solubility of lipophilic drugs, which increases drug exposure and may attenuate the effects of food on the oral bioavailability of drugs with poor aqueous solubility. The lidose isotretinoin formulation employs lipids to encapsulate isotretinoin and enhance its absorption in the absence of food; this helps to maintain more consistent plasma isotretinoin levels during treatment, which positively impacts clinical outcomes, compared to conventional isotretinoin.8,33 The United States (US) Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved lidose isotretinoin (Absorica®, Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, Inc., Princeton, New Jersey) in May 2012 for the treatment of severe, recalcitrant, nodular acne in nonpregnant patients 12 years of age or older with multiple inflammatory nodules 5mm or larger in diameter who are unresponsive to conventional therapy, including systemic antibiotics.34 Drug solubility is also related to its particle size because small particles have a larger total surface area relative to an equivalent amount of larger particles, increasing solvent interaction and, thereby, dissolution rate and solubility.31 Therefore, the smaller the particle size, the faster the drug will be absorbed. For isotretinoin, reduction in particle size was achieved by micronization, which can decrease particle sizes down to 10 micrometers (µm) or even to nano sizes.35 The combination of a lipid carrier system with particle size reduction enhances solubility, absorption, and bioavailability of micronized isotretinoin (Absorica LD®; Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, Inc.), thus enabling similar exposure with less medication (Figure 1, Table 1).

Efficacy and safety of these new formulations of isotretinoin were demonstrated in clinical trials (summarized in Table 2).6-8,33,36–38 Lidose isotretinoin and standard isotretinoin had equivalent plasma concentrations in the fed state. However, when the drugs were taken on an empty stomach, the plasma concentration of isotretinoin was significantly greater following administration of the lidose formulation compared to conventional isotretinoin.8 Specifically, in patients receiving lidose isotretinoin while fasting, mean plasma levels of the drug reached 66.8 percent of that observed after administration with a fatty meal; in patients receiving the standard isotretinoin formulation, drug levels in fasting patients reached only 39.6 percent of that observed after administration with a fatty meal.8 Absorption of micronized isotretinoin is superior to that of lidose isotretinoin, as demonstrated by the equivalent blood levels achieved when micronized isotretinoin 32mg and lidose isotretinoin 40mg were taken with food; the greater bioavailability afforded by micronization provides similar isotretinoin exposure despite the lower dose.7 Under fasted conditions, micronized isotretinoin 32mg was absorbed approximately twice as well as lidose isotretinoin 40mg. Micronized isotretinoin 32mg thus provides an alternative option for acne therapy without a stringent food intake requirement.7

Overall, the superior bioavailability of newer formulations of isotretinoin over standard isotretinoin lies in three factors: 1) a lipid-based drug delivery system that resembles a fatty meal, enhancing absorption; 2) higher encapsulation efficiency so that the drug dissolves more easily; and 3) acceleration of dissolution by particle micronization. These features collectively increase gastrointestinal absorption of isotretinoin.

Implications for clinical practice

The availability of lidose isotretinoin and micronized isotretinoin has benefits in clinical practice. First, patient adherence with the prescribed regimen may be improved because of less food dependency, more flexible dosing, and easier integration of acne therapy into the patient’s daily routine. Second, enhanced absorption and bioavailability of these formulations despite dietary variations may help patients achieve optimal cumulative dosing, thereby reducing acne lesions and relapse rates compared to conventional isotretinoin. In a Phase IV study, patients with severe, recalcitrant, nodular acne who received lidose isotretinoin twice daily without food for 20 weeks experienced relapse rates at the low end of published values for conventional isotretinoin for at least 104 weeks post-treatment.6 New formulations of isotretinoin may thus improve clinical outcomes by providing equivalent efficacy with lower dosing and enhanced patient compliance.

Other clinically relevant issues involve confusion about product distinction and consistency with use of the medication. There are several branded generic formulations of oral isotretinoin currently available that have pharmacokinetic profiles similar to that of standard Accutane®, the original branded isotretinoin product marketed by Hoffmann-La Roche, Inc. that is no longer on the market.22 Therefore, pharmacists and patients may question whether these formulations are interchangeable with each other. For conventional formulations, confusion can be prevented by prescribing “isotretinoin” instead of the branded generic name if there is no preference.39 However, lidose isotretinoin and micronized isotretinoin are not interchangeable with conventional isotretinoin or with each other and are not bioequivalent on a mg-to-mg basis, and substitutions may result in underdosing or overdosing.22 To prevent medication errors, healthcare providers must ensure they and their patients are aware that the currently available isotretinoin formulations vary substantially relative to food effect, bioequivalence, and indications to be coadministered with other medication(s).

Conclusion

Newer formulations of isotretinoin for acne treatment avoid the meal requirement of conventional formulations through a lipid-based drug delivery system and micronization technology, thereby achieving better solubility and greater absorption and potentially simplifying dosing. As a result, lidose isotretinoin and micronized isotretinoin not only can improve oral bioavailability and pharmacological bioactivity but also can increase adherence and therapeutic efficacy in patients who are unwilling or unable to consistently take the medication with an HF/HC meal.29 The additional flexibility provided by these options has been a welcome addition to the armamentarium of acne treatment.

References

- Dressler C, Rosumeck S, Nast A. How much do we know about maintaining treatment response after successful acne therapy? Systematic review on the efficacy and safety of acne maintenance therapy. Dermatology. 2016;232(3):371-80.

- Dreno B, Bordet C, Seite S, et al. Acne relapses: impact on quality of life and productivity. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33(5):937-43.

- Gollnick H, Cunliffe W, Berson D, et al. Management of acne: a report from a global alliance to improve outcomes in acne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49(1 Suppl):S1-37.

- Bickers DR, Lim HW, Margolis D, et al. The burden of skin diseases: 2004 a joint project of the American Academy of Dermatology Association and the Society for Investigative Dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55(3):490-500.

- Zaenglein AL, Pathy AL, Schlosser BJ, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(5):945-73.

- Del Rosso J, Gold L, Segal J, Zaenglein A. An open-label, phase IV study evaluating lidose-isotretinoin administered without food in patients with severe recalcitrant nodular acne: low relapse rates observed over the 104-week post-treatment period. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2019;12(11):13-8.

- Madan S, Kumar S, Segal J. Comparative pharmacokinetic profiles of a novel low-dose micronized-isotretinoin 32 mg formulation and lidose-isotretinoin 40 mg in fed and fasted conditions: two open-label, randomized, crossover studies in healthy adult participants. Acta Derm Venereol. 2020;100(1-2):1-7.

- Webster GF, Leyden JJ, Gross JA. Comparative pharmacokinetic profiles of a novel isotretinoin formulation (isotretinoin-Lidose) and the innovator isotretinoin formulation: a randomized, 4-treatment, crossover study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69(5):762-7.

- Williams HC, Dellavalle RP, Garner S. Acne vulgaris. Lancet. 2012;379:361-72.

- Tanghetti E. The role of inflammation in the pathology of acne. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol 2013;6(9):27-35.

- Dreno B, Pecastaings S, Corvec S, et al. Cutibacterium acnes (Propionibacterium acnes) and acne vulgaris: a brief look at the latest updates. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32 Suppl 2:5-14.

- Penso L, Touvier M, Deschasaux M, et al. Association between adult acne and dietary behaviors: findings from the NutriNet-Sante prospective cohort study. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156(8):854-62.

- Khunger N, Kumar C. A clinico-epidemiological study of adult acne: is it different from adolescent acne? Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2012;78(3):335-41.

- Skroza N, Tolino E, Mambrin A, et al. Adult acne versus adolescent acne: A retrospective study of 1,167 patients. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2018;11(1):21-5.

- Tanghetti EA, Kawata A, Daniels S, et al. Understanding the burden of adult female acne. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7(2):22-30.

- Darji K, Varade R, West D, et al. Psychosocial impact of postinflammatory hyperpigmentation in patients with acne vulgaris. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol 2017;10(5):18-23.

- Titus S, Hodge J. Diagnosis and treatment of acne. Am Fam Physician. 2012;86(8):734-40.

- Baldwin HE, Leyden JJ, Webster GF, Zaenglein AL. Challenges in the treatment of acne in the United States. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2015;34 (No. 5S):S81-S94.

- Bettoli V, Guerra-Tapia A, Herane MI, Piquero-Martin J. Challenges and solutions in oral isotretinoin in acne: reflections on 35 years of experience. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2019;12:943-51.

- Alhusayen RO, Juurlink DN, Mamdani MM, et al. Isotretinoin use and the risk of inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based cohort study. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133(4):907-12.

- Crockett SD, Gulati A, Sandler RS, Kappelman MD. A causal association between isotretinoin and inflammatory bowel disease has yet to be established. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(10):2387-93.

- Leyden J, Del Rosso J, Baum E. The use of isotretinoin in the treatment of acne vulgaris – clinical considerations and future directions. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol 2014;7(2 Suppl): S3-S21.

- Faghihi G, Mokhtari F, Fard N, et al. Comparing the efficacy of low dose and conventional dose of oral isotretinoin in treatment of moderate and severe acne vulgaris. J Res Pharm Pract. 2017;6(4):233-8.

- Del Rosso JQ. Status report on oral isotretinoin in the management of acne vulgaris: why all the discussion about drug absorption and relapse rates? Current Dermatology Reports. 2013;2(3):177-80.

- Rao P, Bhat R, Nandakishore B, et al. Safety and efficacy of low-dose isotretinoin in the treatment of moderate to severe acne vulgaris. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59(3):316.

- 26Colburn WA, Gibson DM, Wiens RE, JJ. H. Food increases the bioavailability of isotretinoin. J Clin Pharmacol. 1983;23(11-12):534-9.

- Zeichner J. Optimizing absorption of oral isotretinoin. Practical Dermatology. 2019(July):73-4.

- Peltzer K, Pengpid S. Trying to lose weight among non-overweight university students from 22 low, middle and emerging economy countries. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2015;24(1):177-83.

- Tan J, Knezevic S. Improving bioavailability with a novel isotretinoin formulation (isotretinoin-Lidose). Skin Therapy Lett. 2013;18(6):1-3.

- Vyas A, Kumar Sonker A, Gidwani B. Carrier-based drug delivery system for treatment of acne. ScientificWorldJournal. 2014;2014:276260.

- Kanikkannan N. Technologies to improve the solubility, dissolution and bioavailability of poorly soluble drugs. Journal of Analytical & Pharmaceutical Research. 2018;7(1):00198.

- Kalepu S, Manthina M, Padavala V. Oral lipid-based drug delivery systems – an overview. Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica B. 2013;3(6):361-72.

- Webster GF, Leyden JJ, Gross JA. Results of a Phase III, double-blind, randomized, parallel-group, non-inferiority study evaluating the safety and efficacy of isotretinoin-Lidose in patients with severe recalcitrant nodular acne. J Drugs Dermatol. 2014;13(6):665-70.

- ABSORICA® (isotretinoin) capsules, for oral use. ABSORICA LD™ (isotretinoin) capsules, for oral use. Full prescribing information. Cranbury, NJ: Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, Inc. 2019.

- Joshi J. A review on micronization techniques. Journal of Pharmaceutical Science and Technology. 2011;3(7):651-81.

- Strauss JS, Leyden JJ, Lucky AW, et al. Safety of a new micronized formulation of isotretinoin in patients with severe recalcitrant nodular acne: A randomized trial comparing micronized isotretinoin with standard isotretinoin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45(2):196-207.

- Strauss JS, Leyden JJ, Lucky AW, et al. A randomized trial of the efficacy of a new micronized formulation versus a standard formulation of isotretinoin in patients with severe recalcitrant nodular acne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45(2):187-95.

- Zaenglein A, Segal J, Darby C, Del Rosso J. Lidose-isotretinoin administered without food improves quality of life in patients with severe recalcitrant nodular acne: an open-label, single-arm, phase iv study. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2020;13(9):15-20.

- Leon S. Optimizing isotretinoin treatment: keys to successful prescribing and management. Practical Dermatology. 2015(April):30-5.

- Layton A. The use of isotretinoin in acne. Dermato-Endocrinol. 2009;1(3):162-9.