by Kyle D. Klingbeil, MD, and Raymond Fertig, MD

by Kyle D. Klingbeil, MD, and Raymond Fertig, MD

Dr. Klingbeil and Dr. Fertig are with the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine in Miami, Florida. Dr. Fertig is also with the Department of Dermatology and Cutaneous Surgery at the University of Miami in Miami, Florida.

Funding: No funding was provided.

Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

Abstract: The objective of this systematic review was to investigate the etiologies of hair loss of the eyebrow and eyelash that required hair transplantation, the optimal surgical technique, patient outcomes, and common complications. A total of 67 articles including 354 patients from 18 countries were included in this study. Most patients were women with an average age of 29 years. The most common etiology requiring hair transplantation was burns, occurring in 57.6 percent of cases. Both eyebrow and eyelash transplantation use follicular unit transplantation techniques most commonly; however, other techniques involving composite grafts and skin flaps continue to be utilized effectively with minimal complication rates. In summary, many techniques have been developed for use in eyebrow/eyelash transplantation and the selection of technique depends upon the dermatologic surgeon’s preferences and the unique presentations of their patients.

Keywords: Follicular unit transplantation, follicular unit extraction, composite grafting, tempoparietal fascial flaps, frontal scalp skin flaps, secondary vascularized hairy skin flaps, V-Y advancement pedicle flaps

J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2018;11(6):21–30

Introduction

Whether it’s the desire to make the eyebrows appear fuller or the need to restore facial aesthetics following an accident, hair transplantation remains a safe and permanent treatment option for patients. The procedure of hair transplantation involves the transplantation of individual hair follicles, most commonly using the follicular unit transplantation (FUT) technique1, along with several available variations including partial longitudinal (PL-FUT)2,3 and de-epithelialization (DE-FUT).4–5 The harvesting of donor hair follicles can be accomplished by amputating a strip of hair-baring skin called strip harvesting or by removing each follicle individually via follicular unit extraction (FUE). Other techniques besides FUT do exist; however, they are applied less commonly in eyebrow transplantation.6,7 They include composite grafts (CGs) and skin flaps. The eyelid represents another location in which hair transplantation remains a superior treatment option for patients who lack sufficient eyelashes.2,8 The procedure of hair transplantation for eyelashes is similar to that of eyebrows, using the FUT technique most commonly. CGs can also be used, especially in patients demonstrating a complete loss of eyelashes.9–12

We conducted a systematic review of the literature involving the transplantation of eyebrows and eyelashes to investigate the etiologies of hair loss requiring transplantation, optimal surgical techniques, patient outcomes, and common complications.

Materials and Methods

Literature search. We performed a MEDLINE (PubMed) search, without language or time restrictions, to identify cases of eyebrow and eyelash transplantation described in the literature. The following MEDLINE search terms were used: eyebrow transplantation, eyelash transplantation, eyebrow graft, eyelash graft, eyebrow follicular unit transplantation, eyelash follicular unit transplantation, eyebrow follicular unit extraction, eyelash follicular unit extraction, eyebrow reconstruction, and eyelash reconstruction. References of the included studies were reviewed for any potentially eligible studies, which were then included in our database. Articles reporting data on identical participants were considered to use an overlapping population, under which circumstances the data were extracted from the highest-quality study. Published abstracts were included only if sufficient data were reported.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria. The following criteria were used for inclusion: 1) full text available; 2) surgical technique involving at least one specified form of hair transplantation; 3) hair transplantation of the eyebrow, eyelash, or both; 4) outcomes of the patient(s) provided; and 5) the presence or absence of complications.

Articles were excluded from the analysis if they met any of the following exclusion criteria: 1) commentaries or editorials; 2) animal or in-vitro studies; 3) studies involving orbit enucleation or exenteration; or 4) studies of frontal scalp amputation involving the eyebrows.

Data extraction and quality assessment. All data were extracted using a standardized extraction form. The following data points were obtained from clinical studies: the first author, publication year, country, study design, sample size, sex, mean age, etiology of hair loss, intervention technique, harvest technique, skin/hair graft location, follow-up duration, and comparable outcomes and complications. The level of evidence of each study was then graded from high to very low according to the American College of Physicians study quality grading system, which is an adaptation of the classification developed by the Grades of Recommendation Assessment, Development and Evaluation workgroup.13 This system rates quality of studies in accordance with the underlying methodology in four categories: 1) high, including randomized trials or double-upgraded observational studies; 2) moderate, including downgraded randomized trials or upgraded observational studies; 3) low, including double-downgraded randomized trials or observational studies; and 4) very low, including triple-downgraded randomized trials or downgraded observational studies or case series/case reports.

Studies can be downgraded in the presence of factors that decrease the quality level of a body of evidence. These include the following:

- Serious limitations (-1) or very serious limitations (-2) to the overall study quality

- Indirectness of evidence (indirect population, intervention, control, outcomes) to some (-1) or a major (-2) degree

- Unexplained heterogeneity or inconsistency of results (-1)

- Imprecision or scarcity of results (wide confidence intervals) (-1)

- High probability of publication bias (-1)

Studies can also be upgraded in the presence of factors that may increase the quality level of a body of evidence. These include the following:

- Strong evidence of association—significant relative risk ?2 or ?0.5 (+1)

- Very strong evidence of association—relative risk ?5 or ?0.2 (+2)

- Evidence of a dose response gradient (+1)

- Assessment of confounders would decrease effect (+1)

Results

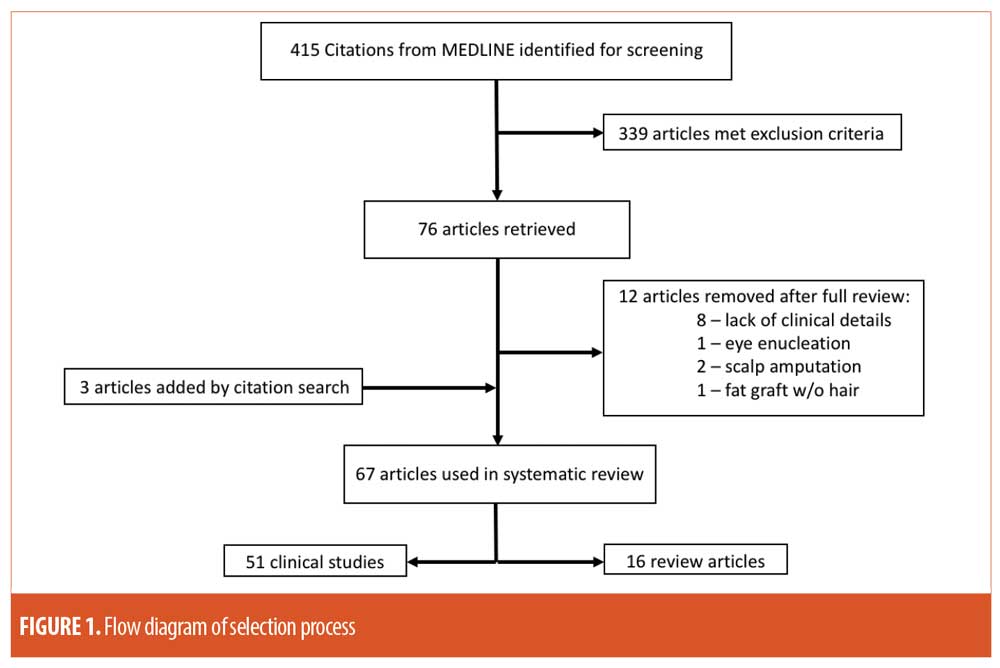

A total of 415 articles were identified by the initial searches, of which 339 articles met the exclusion criteria. Full publication reviews were then conducted on the remaining 76 articles. Eight articles were removed due to a lack of clinical details, including failure to mention surgical techniques, patient outcomes, and/or frequency of complications. Two articles were removed because of the presentation of frontal scalp amputation involving the eyebrows, in which the management was simply re-approximation. An article was also removed due to the presentation of orbit enucleation. Finally, after a full review of citations, three additional articles were added to the database. A total of 67 articles were included in the systematic review, 51 of which were clinical studies, and included 24 case reports, 25 case series, and two clinical trials; the additional 16 were review articles. A flow diagram of the selection process is shown in Figure 1.

A total of 354 patients from 18 countries were included in the systematic review. Of the articles reporting sex, 140 patients were male and 151 were female. The average age of patients, when available, was 29.01 years old.

Here, we present the current available information on common causes of eyebrow or eyelash loss that requires surgical transplantation, the various techniques of hair transplantation, patient outcomes, reported complications, and appropriate follow-up details.

Etiology of Hair Loss Requiring Hair Transplantation

The etiology of hair loss is an important factor to consider when evaluating patients for the possibility of hair transplantation. Hair loss can be physiologic, as seen in normal aging, or iatrogenic as in chronic hair plucking or laser removal procedures. Burns, trauma, and surgical excision of adjacent skin are other common primary causes of hair loss. Secondary causes of hair loss also occur, albeit much less frequently. For example, the sign of Hertoghe is the observation of thinning or total loss of the lateral third of the eyebrow, classically seen in cases of hypothyroidism.1 Secondary causes should be ruled out or corrected before hair transplantation can be considered. After review of the literature, the etiology and frequency of hair loss in the published cases of eyebrow and eyelash transplantation were organized in Table 1.

Eyebrow Transplantation Overview

Hair transplantation techniques have evolved dramatically over the last half-century. From the previous era of unsightly punch grafting to the state-of-the-art FUT, which is capable of achieving consistently natural-looking results, hair transplantation has certainly come a long way. The number of techniques has now grown into an arsenal, from which cutaneous surgeons may choose, allowing them to cater to each unique patient. The three major techniques utilized for eyebrow transplantation include FUT, CG, and skin flaps. Variations of FUT include PL-FUT and DE-FUT. Variations of skin flaps include tempoparietal fascial flaps (TPFFs), frontal scalp skin flaps (FSSFs), secondary vascularized hairy skin flaps (SVHSFs), and V-Y advancement pedicle flaps (VYPFs).

FUT in eyebrow transplantation. FUT has become the gold standard for eyebrow transplantation since its introduction in the early 1990s. This technique involves the transplantation of naturally occurring groups of one to four hairs, called follicular units. This enables cutaneous surgeons to transplant thousands of grafts in a single session, resulting in the restoration of a natural, fuller brow.

The first step of FUT involves the harvesting of hair follicles. The most commonly used harvesting technique involves the excision of a small elliptical strip of skin, usually from the occipital scalp, called strip harvesting.2,14–21 The occipital region is most commonly used because it is known to be the last area of the scalp to be affected by hair loss.2,8,15–18,21–24 Some studies have used skin from the contralateral eyebrow with similar success.15,25 Once the skin strip has been excised, surgical assistants use stereomicroscopic dissection to remove individual follicular units. The main disadvantage of this is the presence of a sizable donor scar. Most patients do not notice the scar after their hair regrows, but scar formation can be an issue for those with shorter hairstyles, tight scalps, or those who develop hypertrophic scars.26

Another common FUT harvesting technique is FUE. This technique has recently been developed as an alternative to strip harvesting, by eliminating the presence of a large donor scar. The procedure involves making a submillimeter punch incision surrounding a single follicular unit extending into the dermis. The follicles are then extracted individually by a pair of fine forceps, leaving an indiscernible donor scar.26 Newer methods include automated handheld drills, extraction tools, and robotic methods.1 FUE provides the ability to selectively choose the size of the follicular units for transplantation, ranging from one hair follicle/unit for thin eyebrows to four hair follicles/unit for maximum density. The main disadvantage of FUE is increased operating time, as it is far more time-consuming to complete than strip harvesting. Another disadvantage is the requirement of large areas of donor hair to be clipped to 2mm in length in preparation for FUE, resulting in significant short-term cosmetic changes. In addition, only about 60 percent of patients are candidates for FUE.17 Patients are excluded if the extraction of follicles is difficult, including frequent fragmentation of hair shafts or transection of hair follicles. On the other hand, a unique benefit of FUE is the ability to extract hair follicles from regions beyond the occipital scalp, allowing for the ability to precisely match the density of the eyebrow. Studies have used a variety of donor regions for FUE including the occipital scalp,3–5,8,27–29 nape and periauricular area (NPA),24 and leg hair.30

Once harvesting is completed, recipient sites on the eyebrow are then created using a high-gauge needle, with careful attention paid to the orientation of hair growth. The surgeon then transplants each follicular unit into the recipient sites based on the location and orientation of the recipient hairs. The eyebrow can be described in three anatomic segments: the head, the body, and the tail. The hair orientation and density is unique to each segment. Experts advise single hair units to be used in the head and tail, while follicular units with two hair shafts are better for the brow body.31 Significant variability occurs among ethnicities and sex and must be kept in mind during hair transplantation. For example, Caucasian subjects are known to have the highest density of hair follicles at up to 100 follicular units/cm2.1 Asians tend to have the thickest follicle caliber.31 Women’s eyebrows tend to have a higher arch, whereas men’s eyebrows tend to be more flat, with a less-defined arch.1

The outcomes after FUT are excellent in most cases, making it the gold standard for eyebrow transplantation. The majority of hair transplantation studies base their outcomes on the patient’s satisfaction. Some studies include objective measures as well, most commonly using follicular unit mean survival percentage.2,8,18,20,21,27,28,32 Almost all patients have a follicular mean survival percentage greater than 75 percent. Cases of lower follicular mean survival tend to occur in patients with burn injuries or significant scarring. For example, Motamed et al6 described poor outcomes in two patients with severe burns who underwent FUT. In addition, Toscani et al10 reported similar poor outcomes in two burn patients who underwent FUT, with 60 percent mean graft survival.

FUT remains the most common technique to be used in eyebrow hair transplantation. Its method includes several varieties of harvesting techniques, including scalp harvesting and FUE. The outcomes for FUT are excellent in most cases, resulting in high patient satisfaction. The main disadvantages of this technique, however, include the lengthy procedure time and high likelihood of needing additional hair transplantation sessions to achieve satisfactory results. In some patients, such as those with burn injuries, FUT has lower graft survival, necessitating additional FUT sessions. A summary of the published work regarding the use of FUT in eyebrow transplantation can be found in Table 2.

De-epithelialization of extracted follicular units for eyebrow transplantation. A recent variation of FUT includes DE-FUT. By removing the epithelium surrounding a follicular unit, the graft becomes less bulky, allowing cutaneous surgeons to place them in recipient sites with less manipulation, leading to less tissue damage and lower rates of scar formation. A case series of DE-FUT by Miao et al3 described positive results with DE-FUT, with all patients expressing satisfaction with the long-term outcomes.

Separately, a clinical trial by Omranifard et al2 compared FUT alone to DE-FUT. The study included 31 cases of eyebrow transplantation, 16 in the FUT group, and 15 in the DE-FUT group. The comparison of each technique was based on the number and percentage of follicular units, scar formation based on the Vancouver score, hair orientation, and overall patient satisfaction. The mean percentage of transplanted follicular units in eyebrows at six months postoperation was found to be significantly higher with DE-FUT versus FUT (85.13±7.5 vs. 69.91±9.94; p=0.00). The severity of scar formation was assessed by the Vancouver score. The score ranged from 0 to 13 based on scar characteristics including vascularity, pigmentation, pliability, and height.2 Higher values correlate with the severity of scar formation. The DE-FUT group was found to have a significantly lower score compared to FUT alone (2.6±0.82 vs. 4.56±1.2, p=0.00). Hair orientation was based on photographs of the hair transplants classified as normal, near-normal, or abnormal as graded by a blinded scorer. DE-FUT resulted in significantly more normal-appearing follicular units after eyebrow transplantation when compared to FUT alone (p=0.01). Patient and surgeon satisfaction were measured by the Likert satisfaction scale, ranging from very unsatisfied, unsatisfied, and satisfied to very satisfied. Both the patient and surgeon satisfaction were significantly higher for the DE-FUT group (p=0.00).

The evidence for the use of DE-FUT has shown significantly better results with both eyebrow and eyelash transplantation when compared with FUT alone. Its application should be considered by cutaneous surgeons seeking hair transplantation via FUT.

Partial longitudinal follicular unit transplantation for eyebrow transplantation.Another known variation of FUT is PL-FUT. This technique involves the partial dissection of follicular units, allowing both the recipient follicular unit and donor follicular unit to survive and produce hairs. It takes advantage of the follicular stem cells present within the follicular unit. The first step involves shaving and disinfecting the donor site. Then, the grafts are extracted using a 0.6mm needle carefully placed in the center of an individual follicular unit, allowing the extraction of a viable, partial follicular unit. Two case series by Gho et al4,5 involving burn victims used PL-FUT, with consistent donor and recipient graft survival demonstrated both in patients with significant burns and those simply desiring a fuller brow.

The PL-FUT represents the first method with the ability to produce two hair follicles from one, providing a unique opportunity for patients with minimal donor hair, such as those with significant burn injuries. Future adaptation of this technique by cutaneous surgeons is required to strengthen the evidence of its outcomes.

Composite grafts in eyebrow transplantation.Large skin defects involving the eyebrow cannot be replaced by FUT; therefore, these patients require a different technique for eyebrow transplantation. Common causes of such skin defects include traumatic avulsion or surgical excision of an adjacent tumor. The use of full-thickness CGs provides an option for transferring thousands of hair follicles in a single operation and has been in use since the 1960s. The main advantage of this technique is the ability to select from a variety of donor sites, allowing cutaneous surgeons to match the follicle density to that of the eyebrow. Donor sites from previous studies include the occipital scalp,6,33 the NPA,34,35 and the sideburns.36 Major disadvantages of CG include the risk for graft failure; hyperpigmentation of graft skin, especially in Caucasian subjects; and the absence of hair growth at graft borders. The major limitation of this technique is its dependency on the vascularity of the recipient site; thus, patients with severe scarring or atrophic tissue might not be candidates. CG has been combined with FUT in some cases. For example, the case study by Vachiramon et al35 used FUT as an adjunct therapy to CG in a patient who had experienced a traumatic partial avulsion of the right eyebrow. The addition of FUT provided precise hair transplantation to the borders of the CG, resulting in satisfactory results as judged by the cutaneous surgeon and patient at the six-month follow-up.

The outcomes of CG eyebrow transplantation tend to provide satisfactory results. To our knowledge, only two cases of CG failure for eyebrow transplantation have been previously described.37,38 CG has been shown to have optimal results for eyebrow transplantation, especially in patients who have experienced a traumatic avulsion or who have undergone an adjacent tumor excisional procedure. A variety of donor sites have been successfully used, expanding the possible options for grafting. A summary of published work regarding the use of CG for eyebrow transplantation can be found in Table 3.

Skin flaps in eyebrow transplantation. The last major technique for eyebrow transplantation involves the use of regional skin flaps. There are four types of skin flaps used during eyebrow transplantation: TPFFs, FSSFs, SVHSFs, and VYPFs. Unlike grafts, skin flaps carry their own blood supply and therefore are not dependent on the quality of vasculature in the recipient bed. This is advantageous in cases wherein the wound bed is not amenable to grafting by FUT or CG. In addition, donor skin in close proximity to the recipient site will more closely resemble its appearance, allowing for optimal cosmetic results. The major limitations of this technique include a complex and time-consuming procedure, along with extensive dissection and unnatural hair-growth direction of the repositioned skin flap.7 For these reasons, skin flaps are typically reserved for male patients with high hair follicle density and in patients in whom other techniques have failed.5,39 The most commonly used variations of skin flaps are discussed below.

Skin flaps originating from the temporal scalp are based on the branches of the superficial temporal artery and are known as TPFFs. First described by Raffaini and Costa40 for the reconstruction of the eyebrow, this technique has gained marginal recognition among cutaneous surgeons. It is believed that the complexity of the superficial temporal anatomy, the requirement of multiple stages, and expertise required to perform such operations have limited its use.41 Nonetheless, some surgeons continue to perform this technique. Ceran et al42 performed TPFF in a 22-year-old male patient after a tumor of the left eyebrow was completely excised. The graft survived completely, with excellent color and texture balance. Other studies using TPFF techniques have reported similar positive results.6,41,43–45

A variety of unique TPFF techniques have been described in the literature. Bozkurt et al46 successfully performed TPFF to reconstruct an eyebrow and ipsilateral eyelid with a functioning lacrimal duct in a patient with severe burns. In a case with bilateral eyebrow loss, Kajikawa et al37 performed a unilateral extended TPFF procedure with two skin islands to reconstruct both eyebrows. Motomura et al47 performed a TPFF procedure using intermediate hair follicles from the frontal hairline and, in one of the patients, the reconstructed eyebrow ceased to grow after one year, preventing the need for frequent trimming. Scevola et al48 applied intense pulsed light as a synergistic therapy to TPFF, refining the hair borders for optimal cosmetic results. In a new study by Pang et al,49 soft tissue expanders were implanted in the region of the posterior branch of the superficial temporal artery and subsequently dilated until the density of hair follicles in the expanded scalp matched that of the healthy eyebrow prior to performing TPFF. The major disadvantage of using expanders is the marked deformity of the scalp between surgical stages, which might not be tolerated by most patients.

A clinical trial by Omranifard et al7 compared TPFF to a subcutaneous pedicle island flap approach derived from the frontal muscle fascia, sometimes known as FSSF. They enlisted 40 patients with unilateral eyebrow defects, 20 of whom were placed in the TPFF group and 20 in the FSSF group. The comparison of techniques was assessed by the direction of donor hairs, the presence of complications, and patient satisfaction. The FSSF technique resulted in a significantly more accurate direction of donor hairs when compared to TPFF (p=0.03) as assessed by a blinded cutaneous surgeon. No significant differences in the rate of complications were present. Patient satisfaction, assessed by a five-point scale, was found to be significantly higher with FSSF (p=0.002). The FSSF operation was also found to take about 20 minutes less to complete than TPFF.

Several other cases of FSSF have been reported in the literature with satisfactory results.50–52 A case described by Kim et al50 involved a 44-year-old male patient who suffered a left eyebrow avulsion following a physical assault. The cutaneous surgeon used the contralateral eyebrow as a skin flap donor, isolating the supraorbital vessels to be used as the flap pedicle. The donor supraorbital vessels were then anastamosed to the recipient supraorbital vessels. Complete graft survival was achieved with preservation of the natural hair direction.

Secondary vascularized hairy skin flaps (SVHSF) have also been used for eyebrow reconstruction. The procedure involves two stages. The first stage involves harvesting of the inferior epigastric artery and vein followed by anastomosis with the superficial temporal artery and vein. Weeks later, the second stage involves transferring the newly vascularized skin flap into the correct position for eyebrow reconstruction.53 The major advantages of this procedure include the lack of length restrictions commonly seen with TPFF and the ability to perform a skin flap in patients whose superficial temporal artery has been previously damaged by trauma or burn injuries. Several cases of severe burns undergoing SVHSF resulted in satisfactory results.53,54

The final technique utilized for eyebrow reconstruction is VYPF. It has been typically employed for smaller eyebrow defects, providing a reliable healing pattern with robust vascular supply. The main advantages of this technique include the similar color and hair density as the recipient site, the incisional scar being concealed within the eyebrow, and the lack of hair growth preventing the need for frequent grooming. A major disadvantage is its limitation to small lesions, typically less than 2.5cm in size.44 A case by Schonauer et al55 utilized VYPF with extensive skeletonization of the pedicle in order to fill a skin defect greater than 3cm in diameter; however, few cases like this exist with positive results. An algorithm proposed by Liu et al40 attempts to simplify the decision-making when selecting between skin flap techniques for eyebrow reconstruction. For defects measuring greater than half of the entire eyebrow, TPFF is recommended, while, for defects affecting less than half of the eyebrow, VYPF is the preferred choice. Although this algorithm is useful in simplifying the decision-making process, future studies are required to assess its efficacy.

The outcomes for skin flap eyebrow transplantation tend to be satisfactory, both for the patient and the cutaneous surgeon. Only one case of TPFF failure has been described.43 However, because most studies reporting the results of skin flaps are observational studies, it is likely that many cases of graft failure simply go unreported. A summary of published work regarding the use of skin flaps for eyebrow transplantation can be found in Table 4.

Eyelash Transplantation Overview

Hair transplantation techniques for the eyelashes use similar principles to those of the eyebrows, paying close attention to the location and quality of donor hairs. Here, we describe the major techniques utilized for eyelash transplantation and their outcomes reported in the literature. To date, no gold standard currently exists for eyelash hair transplantation.

Follicular unit transplantation in eyelash transplantation. FUT is the most commonly used technique for eyelash transplantation. Most studies use FUE for donor harvesting because of the small number of follicles (35–60) required to replenish the eyelashes.2,8,32,56,57 A variety of donor sites can be used for FUE, including the temporal scalp,32 occipital scalp or NPA,8 and leg hair.57 Skin strip harvesting has also been used in eyelash transplantation, with positive outcomes.2

Unfortunately, scalp hair tends to be straight rather than curly, making the grafts look less natural and increasing the risk for trichiasis. In addition, scalp hairs tend to grow rapidly, necessitating more frequent grooming.57 The use of leg hair has been explored as a potential alternative. In a small study by Umar,57 one patient received FUT using NPA as a donor site and another received FUT using leg hair. Both patients reported positive results at three months after surgery. The patient with leg hair grafts noted slow hair growth, with no trimming required until the fourth month postoperation and every 5 to 6 weeks thereafter. The patient with NPA hair grafts noted much faster hair growth, which required trimming within the second month and every 2 to 3 weeks thereafter. The transplanted leg hair also was more responsive to self-administered curling, preventing the need for a professional perm at a salon. The leg hair also achieved higher graft density when compared with the NPA hair (8.2 grafts/cm vs. 7.2 grafts/cm).

DE-FUT can also be used as variation to FUT in eyelash transplantation. In the study comparing DE-FUT to FUT for eyebrow and eyelash transplantation by Omranifard et al,2 48 cases of eyelash transplantation were reported. There were 22 cases in the FUT group and 26 in the DE-FUT group. Eyelash transplantation resulted in a significantly higher mean survival percentage with DE-FUT compared to FUT (85.57±9.47 vs. 75.10±10.36; p=0.00). Eyelash transplantation also resulted in significantly lower Vancouver scores in the DE-FUT group versus the FUT group, (2.15±0.96 vs. 3.68±1.32; p=0.00). Additionally, both the patient and surgeon satisfaction were significantly higher for the DE-FUT group (p=0.00).

Other reported cases of eyelash transplantation by FUT describe high patient satisfaction. The study by Chatterjee et al32 involved 15 patients with eyelash leukotrichia who underwent FUT eyelash transplantation. Improvement in leukotrichia was assessed at a six-month follow-up, where the number of transplanted follicular units were counted and compared to the number of black hairs that regrew. Ten patients had graft survival rates of between 75 and 100 percent, three had rates of between 50 and 75 percent, one had a rate of between 25 and 50 percent, and one had a rate of less than 25 percent. The graft hairs were noted to be straight in all cases, and patients were recommended to frequently curl them to prevent trichiasis. Jung et al8 applied a similar grading system, noting a graft survival rate of between 75 to 90 percent in one patient who underwent eyelash transplantation.

FUT remains the most commonly used technique for eyelash transplantation. Patient outcomes tend to be satisfactory with rapid results. The limitation of eyelash transplantation is the requirement for curly hair to both protect the eye and prevent trichiasis. Natural curly hairs have been used with positive results as alternatives to scalp hairs. A summary of the use of FUT in regards to eyelash transplantation can be found in Table 5.

Composite grafts in eyelash transplantation.Another commonly used technique for eyelash transplantation is CG, in which the use of thin strips of CG is employed. Although only several cases of CG eyelash transplantation have been reported, the study outcomes appear to be similar to that of FUT.9–12 This technique is primarily used for patients with the complete absence of eyelashes and is advantageous because it can be completed in a single operation while preserving the length and direction of the eyelashes. The optimal location of the donor site continues to be contested. The eyebrow,9,12 sideburns,11 and nasal vibrissae10 are all reported examples of donor sites. One disadvantage of using CG in eyelash transplantation is the production of a linear scar at the donor site. However, most practitioners believe this can be camouflaged by surrounding hair.

Of the 11 reported cases that employed CG for eyelash transplantation, each patient demonstrated complete graft survival in the absence of major complications.9–12 CG also resulted in high patient satisfaction and minimal donor scar formation. In the case using nasal vibrissae by Hata and Matsuka,10 a 36-year-old male patient suffered a traffic accident, resulting in significant scarring of his left upper eyelid and loss of eyelashes. A strip of skin within the nasal vestibule was then excised and transplanted as a CG to the site of the absent eyelashes. The graft resulted in complete survival, with no visible scarring within the nasal vestibule or donor site. A summary of other cases using CG for eyelash transplantation can be found in Table 6.

Eyebrow and eyelash hair transplantation complications. There are a variety of complications associated with hair transplantation involving the eyebrows or eyelashes, the majority of which are simply cosmetic and are not hazardous to the patient. Within the first couple days postoperatively, swelling and bruising at the site of transplantation are commonly reported, but generally resolve spontaneously.18,28,32 Infectious folliculitis has also been observed in the first couple of weeks postoperatively, resolving with appropriate antibiotic therapy.8 Eyelash transplantation specifically can lead to blephoritis32 or trichiasis,56 which, in severe cases, could cause scarring of the cornea with subsequent permanent vision loss.

Those with underlying secondary causes of hair loss have higher risks of complications. In the case of eyebrow transplantation in the presence of alopecia areata, the patient returned eight months later with recurrence of the disease. He was then treated medically by intralesional cortisone injections, which resulted in hair regrowth and positive patient satisfaction.22 In another case of alopecia areata by Civas et al,27 the medial eyebrow transplants failed to grow sufficient hair.

Graft failure, especially in large grafts, such as CG or TPFF, is a severe complication that requires immediate attention. In a case of bilateral TPFF by Lim,43 one flap did not survive, requiring the use of a free flap from the right temporal scalp anastamosed to the left anterior branch of the superficial temporal artery. The second skin flap survived without complications. A case by Neidel38 reported CG necrosis of an eyebrow transplantation requiring immediate amputation and eventual replacement by FUT.

The most commonly associated complications of hair transplantation are cosmetic issues. Graft asymmetry, especially involving the eyebrows, is an unfortunate complication. Most cases are thought to be due to local anesthesia wearing off sooner in one eyebrow, resulting in elevation of the brow during the procedure.58 Cutaneous surgeons must remain vigilant in order to prevent this. It is recommended to only administer local anesthetics at the beginning of the case and to administer a second dose only when absolutely necessary. To ensure equal paralysis, the second dose should be given to the contralateral brow as well.

Post-operative care and follow-up

Following the successful transplantation of hair grafts, postoperative care and diligent follow-up is essential to maximize graft success rates. Immediate postoperative care includes keeping the hair grafts dry for five days after transplantation and providing local antibiotic treatment. These measures ensure proper angulation of hair growth and minimize infection, respectively.58 Perifollicular crusts are commonly present and shed spontaneously within the first couple days, at which point normal washing can be resumed.1 The transplanted follicles might appear pink for some time, usually resolving in a couple weeks for FUT and in several months for composite grafts and skin flaps. The transplanted hairs are expected to shed after two weeks and will begin to grow 4 to 5 months later. For patients with eyelash transplants, they are often advised to rinse the eyelids with distilled water and remove debris gently with the aid of Q-tips.57

Once the hairs start to regrow, they can then be cut, shaved, or left alone as per the patient’s preference. Hair transplants from the scalp grow much faster due to a prolonged anagen phase and might require more frequent grooming.1 Eyelashes must be trimmed and curled to prevent the downward growth of the grafts, which can lead to trichiasis and damage to the corneas.58 Patients can begin eyelash care after the first week. The maximum density of transplanted hair occurs within 8 to 14 months.59 Therefore, additional procedures should be scheduled at least eight months apart.

Appropriate follow-up is essential to prevent or treat complications and also to ensure the highest patient satisfaction. To date, there are no current guidelines regarding the appropriate follow-up frequency and duration following hair transplantation. Previous studies advocate for a postoperative follow-up within one week to assess for early signs of graft failure or infection. The frequency of visits then depends on the patient’s situation and the presence of any complications. The duration of follow-up has been shown to occur anywhere between three months to 10 years.51,56

Conclusion

Hair transplantation is a superior treatment option for patients with significant hair loss or hair defects of the eyebrows and/or eyelashes. The choice of transplant technique is highly dependent on the cutaneous surgeon’s expertise and case presentation; however, most procedures result in positive outcomes with minimum risk of complications. With meticulous follow-up and patient education, complete satisfaction can be achieved.

References

- Tomc CM, Malouf PJ. Eyebrow restoration: the approach, considerations, and technique in follicular unit transplantation. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2015;14(4):310–314.

- Omranifard M, Ardakani MR, Abbasi A, Moghadam AS. Follicular isolation technique with de-epithelialization for eyebrow and eyelash reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;130(3):571–578.

- Miao Y, Fan ZX, Hu ZQ, Jiang JD. Single hair grafts of the hairline to aesthetically restore eyebrows by follicular unit extraction in Asians. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42(11):1300–1302.

- Gho C, Neumann M. Restoration of the eyebrows by hair transplantation. Facial Plast Surg. 2014;30(2):214–218.

- Gho CG, Neumann HA. Improved hair restoration method for burns. Burns. 2011;37(3):427–433.

- Motamed S, Davami B. Eyebrow reconstruction following burn injury. Burns. 2005;31(4):495–499.

- Omranifard M, Doosti MI. A trial on subcutaneous pedicle island flap for eyebrow reconstruction. Burns. 2010;36(5):692–697.

- Jung S, Oh SJ, Hoon Koh S. Hair follicle transplantation on scar tissue. J Craniofac Surg. 2013;24(4):1239–1241.

- de Pochat VD, Costa TV, Castro MP, et al. Eyebrow composite graft for eyelash reconstruction: a case report and review of the literature. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2011;64(9):1232–1234.

- Hata Y, Matsuka K. Eyelash reconstruction by means of strip skin grafting with vibrissae. Br J Plast Surg. 1992;45(2):163–164.

- Hernández-Zendejas G, Guerrerosantos J. Eyelash reconstruction and aesthetic augmentation with strip composite sideburn graft. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;101(7):1978–1980.

- Kasai K. Eyelash reconstruction with strip composite eyebrow graft. Ann Plast Surg. 2008;60(6):649–651.

- Atkins D, Best D, Briss PA, et al. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2004;328(7454):1490.

- da Silva Freitas R, Bertolotte W, Shin J, et al. Combination micrografting and tattooing in the reconstruction of eyebrows of patients with craniofacial clefts. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;24(4):340–432.

- Dudrap E, Divaris M, Bouhanna P. [Hair micrograft technique for eyebrow reconstruction]. Ann Chir Plast Esthet. 2010;55(3):219–224. Article in French.

- Ergün SS, Sahino?lu K. Eyebrow transplantation. Ann Plast Surg. 2003;51(6):584–586.

- Goldman BE, Goldenberg DM. Nape of neck eyebrow reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;111(3):1217–1220.

- Laorwong K, Pathomvanich D, Bunagan K. Eyebrow transplantation in Asians. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35(3):496–503; discussion 503–504.

- Miranda BH1, Farjo N, Farjo B. Eyebrow reconstruction in dormant keratosis pilaris atrophicans. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2011;64(12):e303–e305.

- Toscani M, Fioramonti P, Ciotti M, Scuderi N. Single follicular unit hair transplantation to restore eyebrows. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37(8):1153–1158.

- Wang J, Fan J. [Aesthetic eyebrow reconstruction by using follicular-unit hair grafting technique]. Zhonghua Zheng Xing Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2002;18(2):101–103. Article in Chinese.

- Barankin B, Taher M, Wasel N. Successful hair transplant of eyebrow alopecia areata. J Cutan Med Surg. 2005;9(4):162–164.

- Nilforoushzadeh MA, Adibi N, Mirbagher L. A novel treatment strategy for eyebrow transplantation in an ectodermal dysplasia patient. J Res Med Sci. 2012;17(4):407–411.

- Umar S. Eyebrow transplants: the use of nape and periauricular hair in 6 patients. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40(12):1416–1418.

- Konishi K, Sugimoto I, Kakizaki H, Ichinose A. Reshaping the eyebrow by follicular unit transplantation from excised eyebrow in extended infrabrow excision blepharoplasty. Clin Ophthalmol. 2012;6:247–252.

- Rassman WR, Bernstein RM, McClellan R. Follicular unit extraction: minimally invasive surgery for hair transplantation. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28(8):720–728.

- Civa? E, Aksoy B, Aksoy HM. Hair transplantation for therapy-resistant alopecia areata of the eyebrows: is it the right choice?. J Dermatol. 2010;37(9):823–826.

- Goldman GD. Eyebrow transplantation. Dermatol Surg. 2001;27(4):352–354.

- Tajirian AL, Yelverton CB, Goldman GD. Eyebrow reconstruction after removal of melanoma in situ. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39(9):1385–1389.

- Umar S. Eyebrow transplantation: alternative body sites as a donor source. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71(4):e140–e141.

- Epstein J, Bared A, Kuka G. Ethnic considerations in hair restoration surgery. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2014;22(3):427–437.

- Chatterjee M, Neema S, Vasudevan B, Dabbas D. Eyelash transplantation for the treatment of vitiligo associated eyelash leucotrichia. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2016;9(2):97–100.

- Joethy J, Tan BK. A multi-staged approach to the reconstruction of a burnt Asian face. Indian J Plast Surg. 2011;44(1):142–146.

- Fritz TM, Burg G, Hafner J. Eyebrow reconstruction with free skin and hair-bearing composite graft. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41(6):1008–1010.

- Vachiramon A, Aghabeigi B, Crean SJ. Eyebrow reconstruction using composite graft and microsurgical transplant. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;33(5):504–508.

- Matsuda K, Shibata M1, Kanazawa S. Eyebrow reconstruction using a composite skin graft from sideburns. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2015;3(1):e290.

- Kajikawa A, Ueda K. Bilateral eyebrow reconstruction using a unilateral extended superficial temporal artery flap. Ann Plast Surg. 2003;50(4):416–419.

- Neidel FG. [Hair transplantation for reconstruction of the orbital unit]. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd. 2010;227(1):29–32. Article in German.

- Pensler JM, Dillon B, Parry SW. Reconstruction of the eyebrow in the pediatric burn patient. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1985;76(3):434–440.

- Raffaini M, Costa P. The temporoparietal fascial flap in reconstruction of the cranio-maxillofacial area. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 1994;22(5): 261–267.

- Denadai R, Raposo-Amaral CE, Marques FF, Raposo-Amaral CA. Posttraumatic eyebrow reconstruction with hair-bearing temporoparietal fascia flap. Einstein (Sao Paulo). 2015;13(1):106–109.

- Ceran F, Sagir M, Saglam O, et al. Eyebrow reconstruction after tumor excision by using superficial temporal artery island flap. J Craniofac Surg. 2014;25(6):2263–2264.

- Lim CL. Successful transfer of “free” microvascular superficial temporal artery flap with no obvious venous drainage and use of leeches for reducing venous congestion: case report. Microsurgery. 1986;7(2):87–88.

- Liu HP, Shao Y, Yu XJ, Zhang D. A simplified surgical algorithm for flap reconstruction of eyebrow defects. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2017;70(4):450–458.

- Piccagliani L, Ferrara F, Palmieri B, Mosca D. [Eyebrow reconstruction with a scalp island flap based on the superficial temporal artery]. Chir Ital. 2009;61(5–6):647–651. Article in Italian.

- Bozkurt M, Kulahci Y, Kapi E, Karakol P. A new design for superficial temporal fascial flap for reconstruction of the eyebrow, upper and lower eyelids, and lacrimal system in one-stage procedure: medusa flap. Ann Plast Surg. 2009;63(6):636–639.

- Motomura H, Muraoka M, Nose K. Eyebrow reconstruction with intermediate hair from the hairline of the forehead on the pedicled temporoparietal fascial flap. Ann Plast Surg. 2003;51(3):314–318; discussion 319–320.

- Scevola S, Nicoletti G, Randisi F, Faga A. Refinements in brow reconstruction: synergy between plastic surgery and aesthetic medicine. Photomed Laser Surg. 2014;32(2):113–116.

- Pang XY, Ren J, Xu W, et al. Aesthetic eyebrow reconstruction with an expanded scalp island flap pedicled by the superficial temporal artery. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2017;41(3):563–567.

- Kim KS, Hwang JH, Lee SY. Microvascular eyebrow transplantation. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2011;64(9):e241–e243.

- Koçer U, Ulusoy MG, Tiftikçioglu YO, et al. Frontal scalp flap for aesthetic eyebrow reconstruction. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2002;26(4):263–266.

- Motamed S, Naeeni AF. Nose and eyebrow reconstruction following electrical injury. J Burn Care Res. 2008;29(5):859.

- Mizuno H, Akaishi S, Kobe K, Hyakusoku H. Secondary vascularised hairy flap transfer for eyebrow reconstruction. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2009;62(12):e625–e626.

- Hyakusoku H. Secondary vascularised hair-bearing island flaps for eyebrow reconstruction. Br J Plast Surg. 1993;46(1):45–47.

- Schonauer F, Taglialatela Scafati S, Molea G. Supratrochlear artery based V-Y flap for partial eyebrow reconstruction. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2010;63(8):1391–1392.

- Murchison AP, Wojno TH. Trichiasis after eyelash augmentation with hair follicle transplantation. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;23(4):323–324.

- Umar S. Eyelash transplantation using leg hair by follicular unit extraction. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2015;3(3):e324.

- Epstein J. Facial hair restoration: hair transplantation to eyebrows, beard, sideburns, and eyelashes. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2013;21(3):457–467.

- Avram M, Rogers N. Contemporary hair transplantation. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35(11):1705–1719.