J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2024;17(4):33–36.

J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2024;17(4):33–36.

by Eva Rawlings Parker, MD, DTMH; Carolyn G. Ahlers, MD; and Alexander B. Hicks, MD

Dr. Parker is with the Department of Dermatology at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tennessee, and the Center for Biomedical Ethics and Society at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tennessee. Dr. Ahlers is with the Department of Medicine at Duke University School of Medicine in Durham, North Carolina. Dr. Hicks is with Levy Dermatology in Jackson, Tennessee.

FUNDING: No funding was provided for this article.

DISCLOSURES: The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to the contents of this article.

ABSTRACT: Keratoacanthoma (KA) is a common, low-grade, rapidly growing cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma that presents as an enlarging crateriform nodule, which may spontaneously involute but rarely metastasizes. Immunosuppression, ultraviolet light, viral infection, surgical procedures, and trauma are associated with their development. Overall, tattoo-induced squamous cell neoplasms are infrequently described in the literature. Carcinogenesis is hypothesized to result from trauma caused by the tattooing procedure or a foreign body reaction to the pigment. However, the pathogenesis has not been clearly defined. While most commonly associated with red ink, to date, very few cases of KA forming within black, blue, or multicolored ink tattoos are reported. Herein, we describe a case of KA arising within areas of blue and black pigment in a decorative ink tattoo.

Keywords: Tattoo, cutaneous malignancy, keratoacanthoma, squamous cell carcinoma

Introduction

Keratoacanthoma (KA) is a common low-grade, rapidly-growing cutaneous squamous cell neoplasm that may spontaneously involute but rarely metastasizes.1 The origin of these lesions is still not fully understood, though immunosuppression, ultraviolet (UV) light, viral infection, surgical procedures, and trauma, among other inciting factors, are associated with the development of KA.1 Histologically, differentiation of these lesions from conventional squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) presents a challenge,2 thus when possible, treatment with surgical excision is the gold standard, providing both an acceptable aesthetic outcome and a high negative predictive value.1

Tattoo-induced squamous cell neoplasms are infrequently described in the literature. KA typically presents as a rapidly enlarging crateriform nodule within the zone of tattoo pigment. They are most commonly associated with red ink.3–15 Numerous theories underlying the development of KA within tattoos are suggested, including trauma from the tattooing procedure itself, a foreign body reaction to the pigment, carcinogenic properties of the ink, or a synergistic response between the tattoo pigment and UV as evidenced by the frequent occurrence of these lesions within lower leg tattoos.15–18 However, at present, the exact pathogenesis has not been clearly defined and may in fact be multifactorial.15 While most often associated with red ink, to date, very few cases of a KA forming within black, blue, or multicolored ink tattoos are documented in the medical literature.19,20 In this report, we describe the case of a KA arising from a black and blue ink tattoo.

Case Report

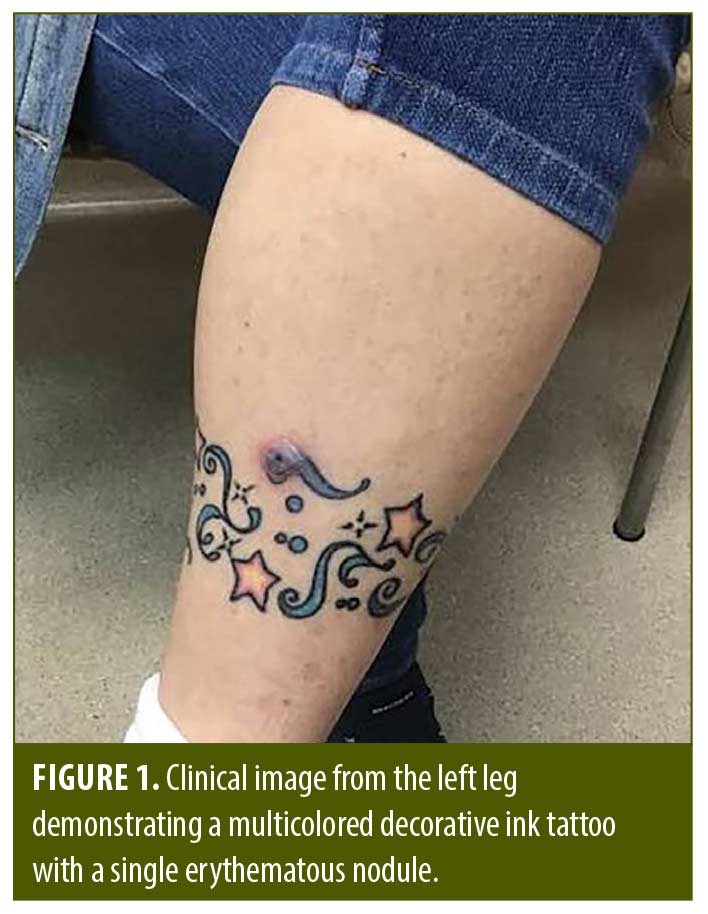

A 62-year-old female with history of hypothyroidism, hypertension, and tobacco use who presented to the dermatology clinic with a two-month history of an enlarging nodule on the left lower leg with symptoms of itching and pain. Two weeks prior to the development of the lesion, the patient had a decorative black and blue permanent ink tattoo placed within the affected area. Of note, she denied any additional exposures within the field, including recent UV exposure, pedicures, trauma, or submersion in hot tubs, pools, lakes, oceans, or other bodies of water. Evaluation of the left lower leg revealed a circumferential, multi-colored permanent ink tattoo with yellow, blue, black, and a small amount of red pigment (Figure 1). Within an area of blue and black pigment on the anterior medial aspect of the leg was a 1.2cm erythematous dome-shaped nodule with central 0.2cm hemorrhagic and keratotic scale crust and surrounding collarette of scale at the base of the lesion (Figure 2). No purulence, edema, induration, or satellite lesions were observed. The remainder of the tattoo was unaffected. The patient had additional older tattoos located on other anatomical sites that were normal appearing and without concerning lesions. The clinical differential at the time of evaluation included tattoo granuloma, foreign body reaction, localized infection, and a neoplastic process. A tangential shave biopsy was performed on the nodule, which was sent for H&E, as well as bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial tissue cultures.

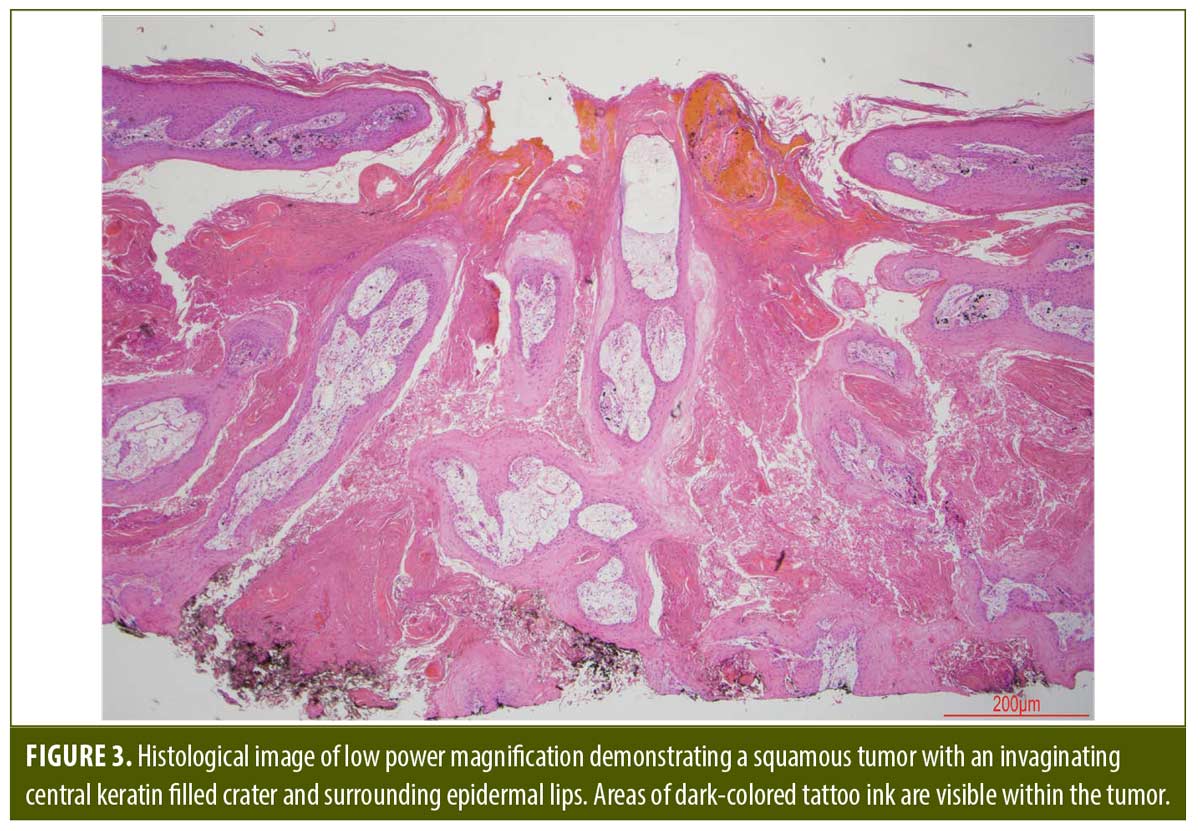

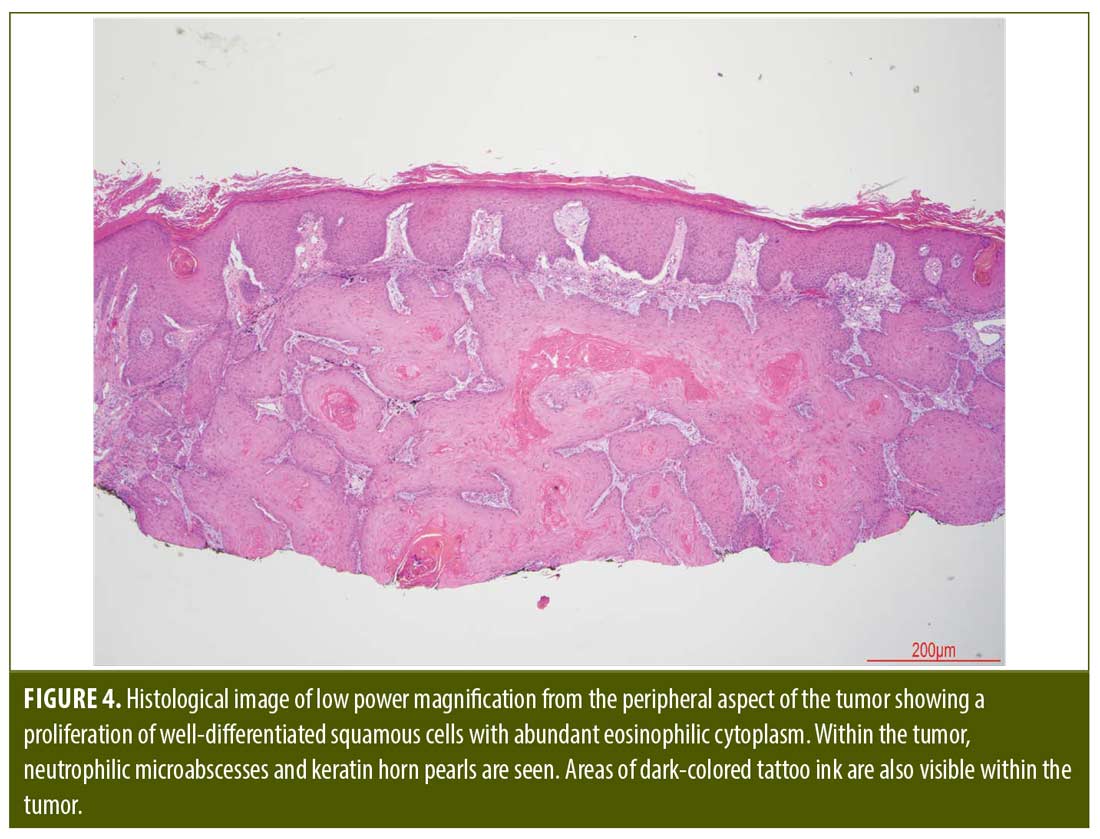

Histologically, the lesion revealed a squamous tumor with an invaginating central keratin filled crater and surrounding epidermal lips as shown in Figure 3. The lesion is composed of a proliferation of well-differentiated squamous cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and enlarged hyperchromatic nuclei (Figures 3 and 4). Within the tumor, the typical intraepidermal neutrophilic microabscesses and keratin horn pearls were noted (Figure 3) along with areas of dark-colored tattoo ink (Figures 3 and 4). These findings were consistent with SCC, keratoacanthoma type, with involved margins. AFB and GMS stains were performed at the time and failed to highlight a causative organism. The tumor was subsequently treated with standard surgical excision without complication.

Discussion

While common among the general population with an estimated prevalence of 24 percent in those aged 18 to 50 years, tattoos are not without risk.21 Complications associated with tattoos include infection, hypersensitivity and granulomatous reactions, phototoxic reactions, pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, and neoplasms, such as lymphoma, SCC, and KA.15,22–27

KA is a distinct entity that was initially described in 1889 by Sir Jonathan Hutchison as a “crateriform ulcer of the face”.28 Cipollaro published the first report of KA occurring within a tattoo in 1973,29 and since that time, other authors have reported KAs and SCCs arising from tattoos, most commonly within those containing red ink.3–15,30,31 The pathogenesis of tattoo-associated KAs is not well understood, but it is hypothesized that trauma induced by tattooing, local inflammation, a component of the ink, UV exposure, and a genetic predisposition may play a role.32,33

The safety of tattoo ink, in general, and its precise role in carcinogenesis is not well understood.16–18 Tattoo pigments may contain carcinogenic compounds including primary aromatic amines, cleavage products of organic azo colorants, and metal oxides.33 In particular, red dye is postulated to act as a co-carcinogen with UV light.34 Mercury sulfide, commonly found in red tattoo ink, is a possible candidate carcinogen, whereas spectroscopy of three red ink tattoo-associated KAs identified the presence of iron and zinc oxide in all three samples and titanium oxide in a single sample.20,32 However, there is a dearth of reports of KA arising from black, blue, or multicolored ink, thus the carcinogenic pathways and ink constituents associated with these pigments have yet to be elucidated.19,20 Despite the link with cutaneous neoplasms and inflammatory skin reactions, the United States Food and Drug Administration does not regulate tattoo ink production.21 Consequently, the specific components within ink preparations that may contribute to the development of tattoo-related adverse cutaneous reactions remains unknown.

Most squamous neoplasms within tattoos present as an enlarging, erythematous papule or nodule with ulceration, scale, induration, or central keratinaceous material. While solitary nodules are most common, multiple lesions at initial presentation or over time have been described. Tattoo age at the time of presentation of cutaneous lesions may vary from weeks to greater than 50 years.21 The presence of innocuous nuclei, infundibulocystic structures, adnexal hyperplasia, and signs of regression on histopathologic examination may aid in the diagnosis and help to differentiate a KA from other variants of SCC.31

Primary management for these neoplasms generally consists of complete surgical excision, with long-term follow-up recommended to monitor for recurrence. Although no reported cases of recurrence after excision of a tattoo-induced KA were identified,21 eruptive KAs occurring adjacent to previous surgical sites are reported.7 Further investigation is paramount to determine the pathomechanisms for cutaneous neoplasms arising within tattoo sites, but in the meantime, patients should continue to receive counsel regarding this potential adverse effect, as well as information about the lack of regulation involved in the production of tattoo inks.

Few reports of a KA arising from a black or blue ink tattoo exist in the medical literature.35,36 This case highlights that KAs, while most commonly associated with red ink tattoos, may also arise within other ink colors. Clinical awareness of this association may allow for dermatologists to more quickly diagnose tattoo-associated KAs. This report additionally underscores the need for further study regarding the safety of tattoo ink components and improved oversight and regulation of this industry.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Jeffrey P. Zwerner, MD, PhD for his assistance with obtaining the histology photos and descriptions.

References

- Kwiek B, Schwartz RA. Keratoacanthoma (KA): An update and review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016 Jun;74(6):1220–1233.

- Cribier B, Asch P-H, Grosshans E. Differentiating Squamous Cell Carcinoma from Keratoacanthoma Using Histopathological Criteria. Dermatol. 1999;199(3):208–212.

- Mitri F, Hartschuh W, Toberer F. Multiple Keratoacanthomas after a Recent Tattoo: A Case Report. Case Rep Dermatol. 2021;13(1):23–27.

- Linares-Gonzalez L, Ródenas-Herranz T, Galvez-Moreno M, et al. Eruptive Keratoacanthomas in a Red Tattoo. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2020;20(3):e372–e373.

- Queen D, Richards LE, Bordone L, et al. Multiple keratoacanthomas arising within red tattoo pigment. Cutis. 2019;104(4):E15–17.

- Sherif S, Blakeway E, Fenn C, et al. A Case of Squamous Cell Carcinoma Developing Within a Red-Ink Tattoo. J Cutan Med Surg. 2017;21(1):61–63.

- Maxim E, Higgins H, D’Souza L. A case of multiple squamous cell carcinomas arising from red tattoo pigment. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2017;3(4):228–230.

- Donnarumma M, Scalvenzi M, Fabbrocini G, et al. Keratoacanthoma occurring in a recent skin tattoo and self-involuted after a punch biopsy. Ital J Dermatol Venerol. 2021;156:75–76.

- Gon A dos S, Minelli L, Meissner MCG. Keratoacanthoma in a tattoo. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15(7):9.

- Giberson M, Rogachefsky A, Lortie C. Finding Chemo for Nemo: Recurrent Eruptive Keratoacanthomas in a Tattoo. Dermatol Surg. 2020;46(12):1771–1773.

- Hoss E, Kollipara R, Goldman MP, et al. Eruptive Keratoacanthomas in a Red Tattoo After Treatment With a 532-nm Picosecond Laser. Dermatol Surg. 2020;46(7):973–974.

- Van Rooij N, Byrom L. A case of multiple keratoacanthomas associated with red tattoo pigment. Australas J Dermatol. 2020;61(4):e463–464.

- Kluger N, Minier-Thoumin C, Plantier F. Keratoacanthoma occurring within the red dye of a tattoo. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35(5):504–507.

- Fraga GR, Prossick TA. Tattoo-associated keratoacanthomas: a series of 8 patients with 11 keratoacanthomas. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37(1):85–90.

- Rahbarinejad Y, Guio-Aguilar P, Vu AN, et al. Pathogenesis, Diagnosis and Management of Squamous Cell Carcinoma and Pseudoepithelial Hyperplasia Secondary to Red Ink Tattoo: A Case Series and Review. J Clin Med. 2023;12(6):2424.

- Simunovic C, Shinohara MM. Complications of decorative tattoos: recognition and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2014;15(6):525–536.

- Kluger N, Koljonen V. Tattoos, inks, and cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(4):e161–168.

- Schmitz I, Prymak O, Epple M, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma in association with a red tattoo. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2016;14(6):604–609.

- Goldenberg G, Patel S, Patel MJ, et al. Eruptive squamous cell carcinomas, keratoacanthoma type, arising in a multicolor tattoo. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35(1):62–64.

- Quinn A, Banney L, Perry-Keene J, et al. Eruptive keratoacanthomas in tattoos. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:317–18.

- Junqueira AL, Wanat KA, Farah RS. Squamous neoplasms arising within tattoos: clinical presentation, histopathology and management. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2017;42(6):601–606.

- Sauvageau AP, Mojeski JA, Bax MJ, et al. Delayed-onset pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia reaction to red tattoo pigment resembling squamous cell carcinoma. JAAD Case Rep. 2019;5(3):222–224.

- Swigost AJ, Peltola J, Jacobson-Dunlop E, et al. Tattoo-related squamous proliferations: a spectrum of reactive hyperplasia. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2018;43(6):728–732.

- Kluger N, Fusade T. [Complications related to tattoo practice]. Rev Prat. 2020;70(3):305–309.

- Boyd AS. Multiple keratoacanthomas arising in a new tattoo. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59(1):e11–e12.

- Badavanis G, Constantinou P, Pasmatzi E, et al. Late-onset pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia developing within a red ink tattoo. Dermatol Online J. 2019;25(5):10.

- Barton DT, Karagas MR, Samie FH. Eruptive Squamous Cell Carcinomas of the Keratoacanthoma Type Arising in a Cosmetic Lip Tattoo. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41(10):1190–1193.

- Hutchinson J. The crateriform ulcer of the face: A form of epithelial cancer. Trans Pathol Soc London. 1889;40:275–281.

- Cipollaro V. Keratoacanthoma developing in a tattoo. Cutis. 1973;11:809–810.

- Kluger N, Minier-Thoumin C, Plantier F. Keratoacanthoma occurring within the red dye of a tattoo. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35(5):504–507.

- Fraga GR, Prossick TA. Tattoo-associated keratoacanthomas: a series of 8 patients with 11 keratoacanthomas. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37(1):85–90.

- Kluger N, Douvin D, Dupuis-Fourdan F, Doumecq-Lacoste J-M, Descamps V. [Keratoacanthomas on recent tattoos: Two cases]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2017;144(12):776–783.

- Colboc H, Bazin D, Moguelet P, et al. Chemical composition and distribution of tattoo inks within tattoo-associated keratoacanthoma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34(7):e313–15.

- Lerche CM, Heerfordt IM, Serup J, et al. Red tattoos, ultraviolet radiation and skin cancer in mice. Exp Dermatol. 2017;26(11):1091–1096.

- Goldenberg G, Patel S, Patel MJ, et al. Eruptive squamous cell carcinomas, keratoacanthoma type, arising in a multicolor tattoo. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35(1):62–64.

- Quinn A, Banney L, Perry-Keene J, et al. Eruptive keratoacanthomas in tattoos. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58(4):317–18.