J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2023;16(7):26–33.

J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2023;16(7):26–33.

by Zoya Diwan, MBBS, BSc, PG Dip Clinical Dermatology; Sanjay Trikha, MBBS, BSc;

Sepideh Etemad-Shahidi, BDS, BSc, RCSEng; Nina Parrish, BSc; and

Christopher Rennie, MBBCh, MRCS

Dr. Diwan is the President of Academic Aesthetics Mastermind Group and the Medical Director at Trikwan Aesthetics in London, United Kingdom. Dr. Trikha is the Vice President of Academic Aesthetics Mastermind Group and the Director at Trikwan Aesthetics in London, United Kingdom. Dr. Etemad-Shahidi is a member at Academic Aesthetics Mastermind Group and a Practitioner at Medicetics in London, United Kingdom. Dr. Rennie is a member of the Academic Aesthetics Mastermind Group and a Director at Romsey Medical Aesthetics in Winchester, United Kingdom. Ms. Parrish is a member of the Academic Aesthetics Mastermind Group and Trikwan Aesthetics in London, United Kingdom.

FUNDING: No funding was provided for this article.

DISCLOSURES: The authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

ABSTRACT: Background. The current popularity of dermal filler treatments as an alternative to invasive surgical cosmetic procedures has led to an increase in filler-related complications. Lip filler treatments are among the most sought-after injectable treatments and a thorough understanding of the complications of lip filler injections, and their management, is essential for any practitioner.

Objective. The aim of this review is to evaluate the current literature on complications secondary to lip augmentation following non-permanent dermal fillers.

Methods. A thorough MEDLINE literature search of keywords, including lip filler, augmentation, injection, filler, dermal filler, and complications, was completed to collate cases of complications secondary to lip filler injections.

Results. Of our 53 cases that were studied, 82 complications were reported. Our review and evaluation of these cases showed that HA filler was most commonly used in this region, alone or in combination with other soft tissue fillers. The majority of complications resulted from HA involvement, however its frequency of use likely accounts for this. Across all three filler types, the most common complication was nodule formation. Other complications, such as migration, discoloration and herpetic outbreaks, have been linked with filler placement in the lip area.

Conclusion. It is clear that filler treatments carry a variety of risks, thus it becomes of utmost importance to truly understand the product we are working with, its properties, its associated risks, and how to manage those risks. We have to ensure that patients are adequately informed about the risks associated, and understand what those risks entail.

Keywords. Hyaluronic acid, complicatios, lip filler, dermal filler, cosmetic complications, lip filler complications.

While cosmetic surgery numbers remain relatively static, there has been an explosive increase in the UK’s non-surgical treatment market. Currently non-surgical treatments including the use of dermal fillers account for nine out of 10 procedures in the UK and are worth £2.7 billion.1

This has coincided with the rise of social media and many younger patients are now seeking non-surgical procedures, seeing these as inexpensive and quick fixes added to their beauty regimens. The use of dermal fillers, particularly for lip augmentation, has become the social norm and while a wide range of ages are seeking treatment, there are serious risks to patients due to the almost completely unregulated nature of the non-surgical aesthetic industry in the UK.2

Dermal fillers are used to restore facial volume or reduce wrinkles to create a younger and more attractive appearance.3 Although these products are efficient and safe, they may trigger some complications. Unfortunately, complications can be encountered by using any injectable product and as such it is important to discuss potential side effects with patients before procedures, even if most are reversible and minor.4

The objective of this review was to evaluate the current literature on complications secondary to lip augmentation following dermal fillers.

Methods

A thorough literature search was completed using search terms: “lip filler”, “augmentation”, “injection”, “filler”, “dermal filler”, “complications”, “complications” or “soft filler complications” or “injectable complications” and “dermal fillers” and “lip filler”, “lip augmentation” or “lip filler” and “complications”. All cases that included human subjects over 18 years old who had non-permanent soft tissue fillers and where the paper was published between 2010 and 2020, were included. If permanent filler was used or if multiple facial treatments were performed in the same sitting as the lip, these patients were excluded. In addition, if the study reported complications due to a cause other than dermal filler or if post-surgical patients were used, these were also excluded.

The group reviewed 38 papers and excluded 19 as they did not meet criteria or spoke in terms of general management of complications as opposed to a specific lip filler complication case/s. We included 19 papers in our results section with 53 appropriate cases. Some papers included multiple cases but we only used the ones that were relevant. For example, Eversole et al5, discussed 12 cases in total in their paper, we excluded three of these as the filler material used was silicone (permanent). In addition, side effects like bruising and acute swelling were also excluded as these do not classify as complications. For example, Yazdanparast et al6, discussed 10 cases and we excluded nine as these described bruising, swelling, and pain which we are not classified as complications. Some papers, while mentioning multiple cases as a whole, only described a few cases in enough detail to include. For example, Turkmani et al7, discussed five cases in the lip in total but only two were described clearly which are included in the results.

Results

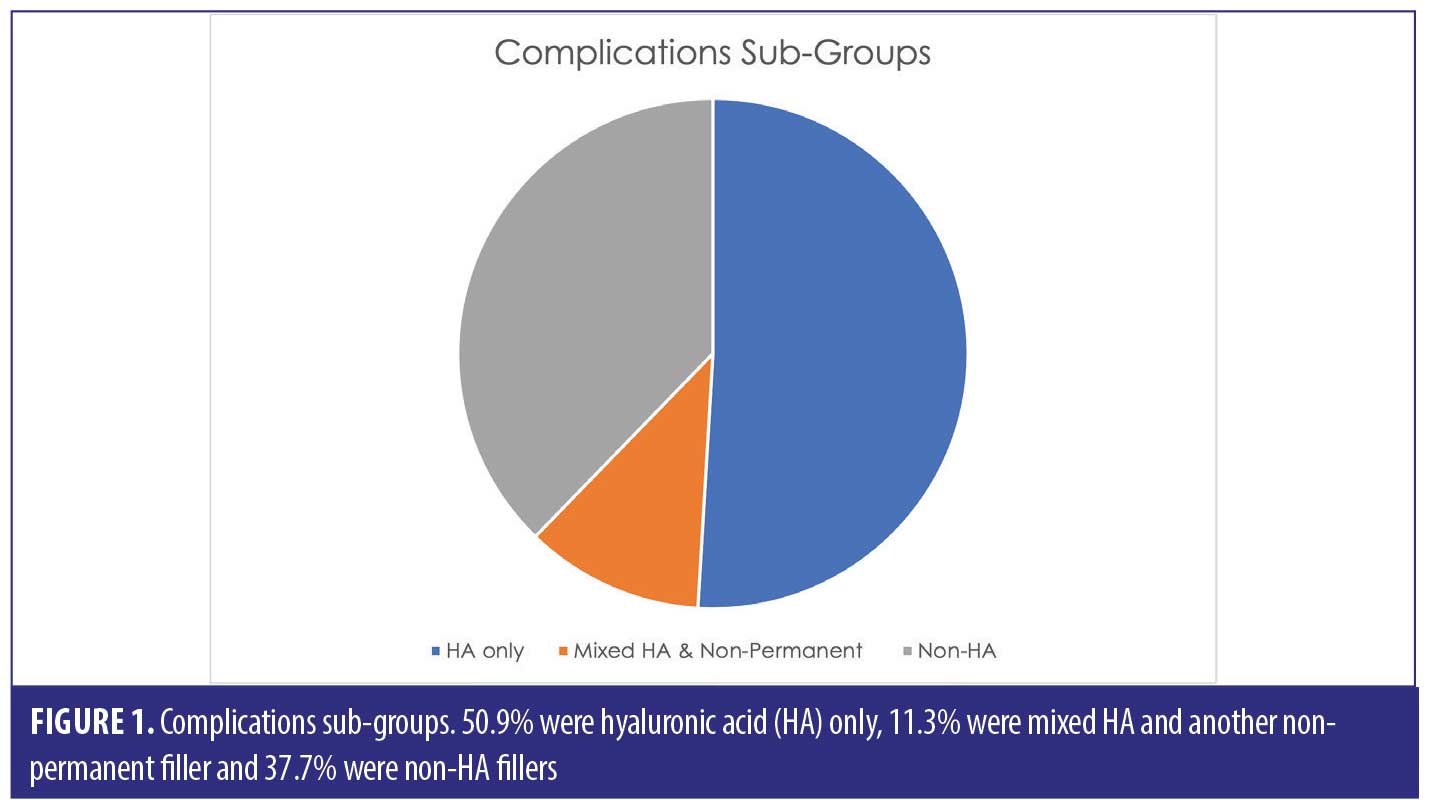

A total of 53 patients were included in this report who suffered a total of 82 complications between them. Table 1 describes each of these cases in detail (Table 1). We have divided this into three groups; HA only, Mixed HA with other non-permanent filler and Non-HA group (includes the unknown material) (Figure 1).

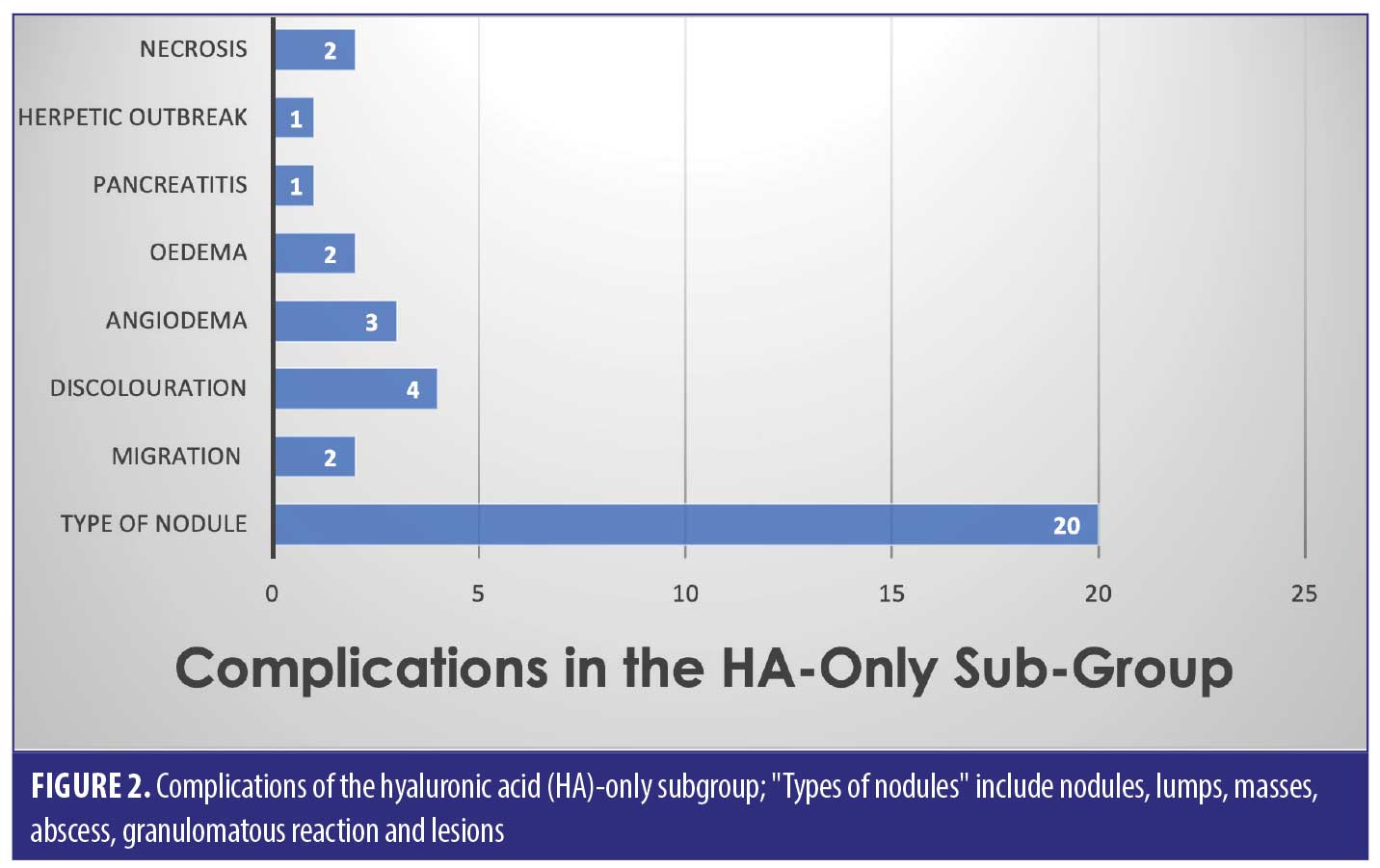

Out of the 53 cases, 27 of the patients (50.9% of sample) had only HA-based fillers in their lips. They suffered 35/82 of the reported complications (42.7%) (Figure 2).

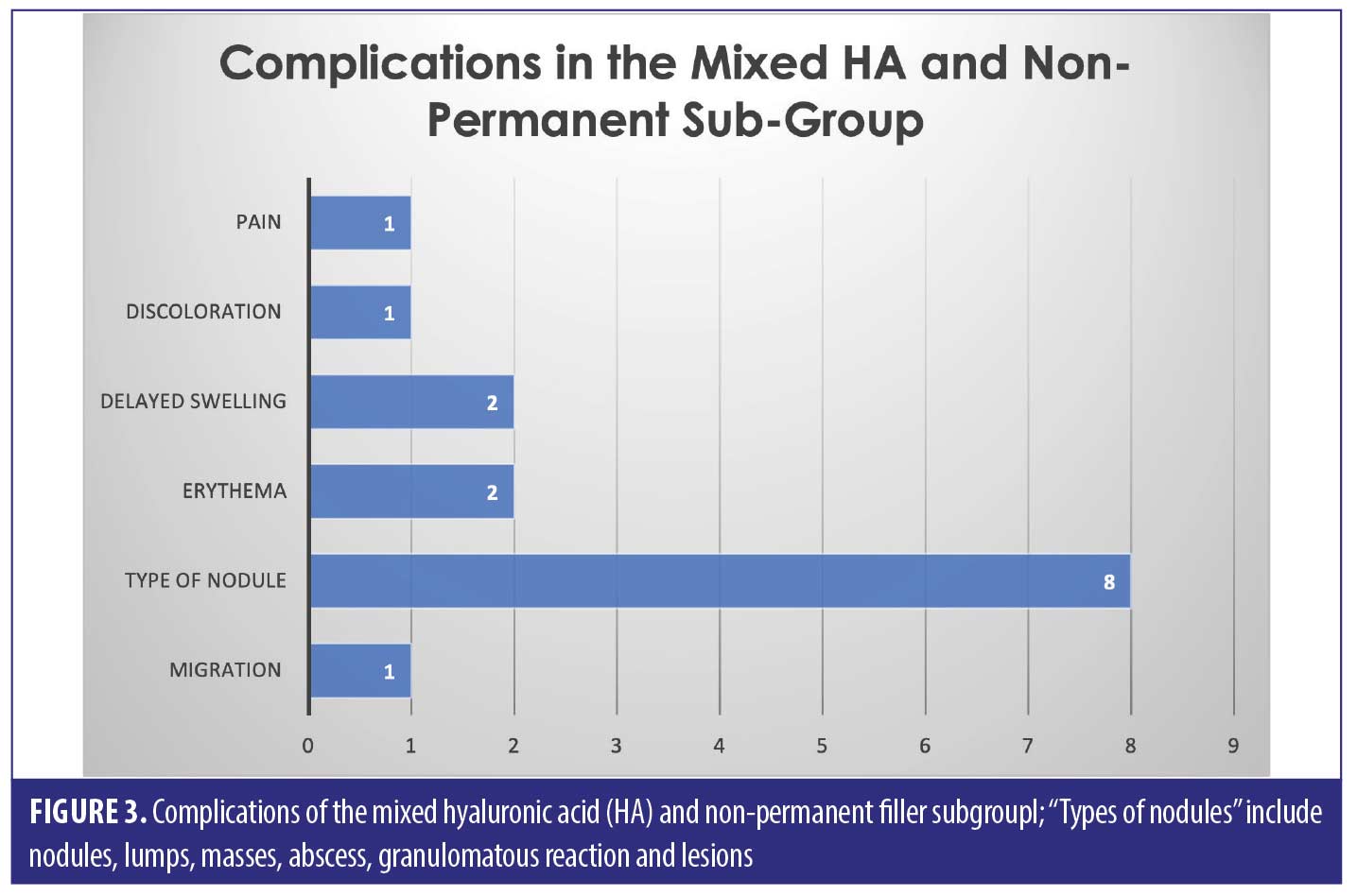

Thirty-three of the patients (62.2% of the sample) had HA involved in their treatment, this may have been in combination with other types of filler over multiple sittings. The combination group along with the purely HA group suffered 50/82 complications (64.1%). The six cases in the combination group who had mixed HA with other non-permanent fillers suffered 15/82 complications between them in total; 18.3 percent (Figure 3).

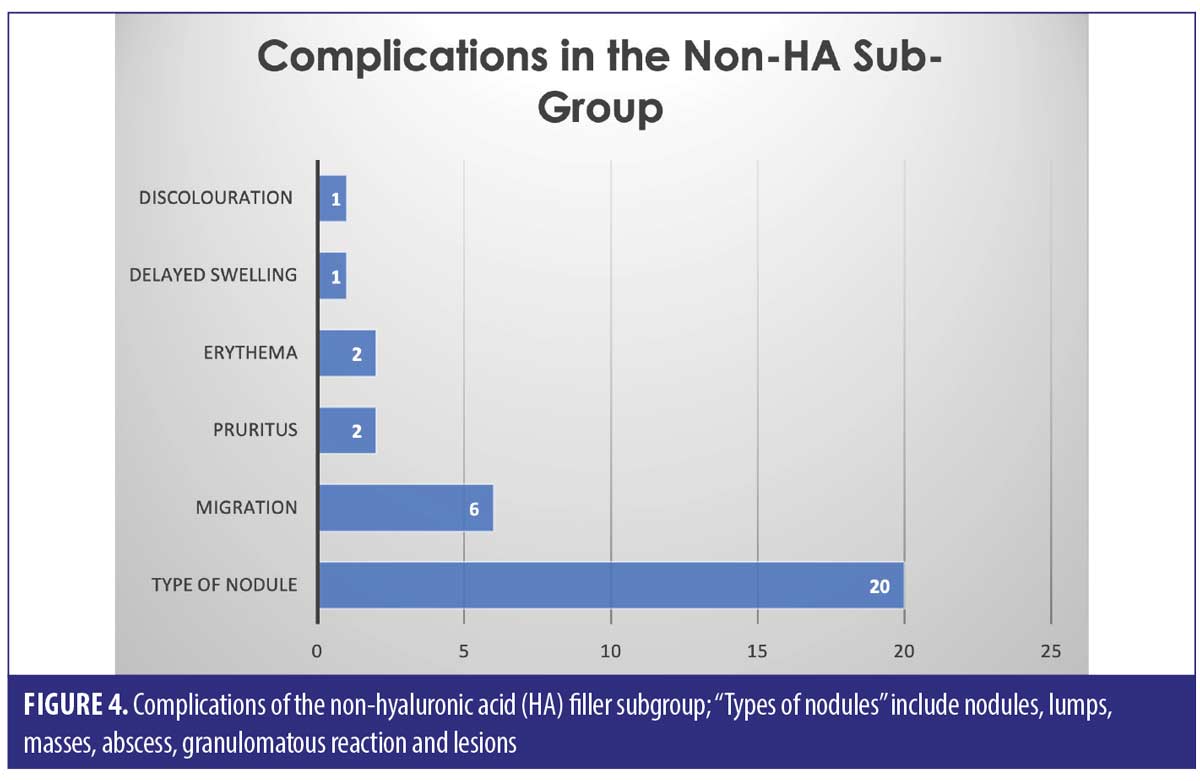

The largest complication category is “types of nodules” which makes up 45/82 total complications (54.9%). These included complications described as nodules, lumps, masses, abscess, granulomatous reaction, and lesions. Eighteen of the 45 (33.3%) complications included as “type of nodule” came from the HA only group. Thirty-two out of 82 complications were seen in the non-HA group (Figure 4). Migration was seen in 9/82 complications in the 53 cases included. Only two out of the nine migration cases came from the 27 HA-only patients. Six out of the nine migration cases came from the 21 cases that did not involve any HA. The two cases of pruritis both came from cases not involving any HA. Four of the five cases of discoloration came from the purely HA group, and the final 1/5 came from the mixed HA group. All cases of discolouration involved HA (4/4).

Zero out of four cases of erythema came from the HA-only group, whereas 1/4 came in the mixed HA and non-permanent filler group. Both cases of necrosis came from the HA-only group, with no other types reporting necrosis in the reviewed literature. The herpetic outbreak was seen in the HA-only group. The isolated case of pancreatitis described after HA fillers in the lips is causality more than direct effect. There were nine cases in total of oedema/swelling/inflammation, with majority in the HA group.

Discussion

The use of dermal fillers is on a significant rise, with new products and methods being constantly developed. It is important that with these new materials and methods, we are able to reduce the frequency and severity of adverse reactions. However, to be able to do as such, it is necessary for us to understand the underlying causes for these complications. Dermal fillers can be divided into permanent and non-permanent (HA) groups. Permanent fillers are usually synthetic or alloplastic, with a very low breakdown rate, if at all.23 This cohort includes silicone and polymethylmethacrylate.

Hyaluronic acid, a non-permanent filler, is classified as a non-sulfated glycosaminoglycan polysaccharide composed of repeating disaccharide units of glucuronic acid and N-acetylglucosamine.14 It is produced by mesenchymal cells, which have no species specificity, hence it is considered to be a biocompatible, non-toxic compound with no risk of immunogenicity. Due to its hydrophilic nature, HA is perfect for dermal cosmetic use, as less product volume is necessary to create a significant change, this is due to the capability of HA to attract and retain water and thus occupy a larger volume relative to its mass.24 HA fillers are cultivated from animal and non-animal sources – the former is retrieved from rooster combs and latter is produced by microbiologic engineering (generated by strep. Equi).14 The non-animal type is cross-linked and much more resistant to hyaluronidase, but less likely to cause allergic reactions. HA is considered an inert and non-immunogenic form of filler, which is usually resorbed between 4 to 6 months, though this can vary in cases with hypersensitivity and foreign body reactions (which can develop anywhere between 6 to 24 months).14

From the 53 cases studied, there is a total of 82 adverse reactions as a result of lip augmentation with fillers. These included HA only dermal fillers, non-HA fillers and mixed HA with non-permanent fillers.

The HA-only filler cohort (50.9% of sample) was responsible for 42.7 percent of the complications. Overall, HA involvement accounted for 62.2 percent of the sample (HA only as well as mixed HA), which resulted in 64.1 percent suffering with complications. We should note that the use of HA filler has more popularity versus non-HA, which is evident in our report, therefore with higher frequency of use, there will most likely be, by default, higher incidences of complications.

Across all three groups of filler types, the most common complication was a “type of nodule” formation (54.9% of the total complications)– this includes “nodules, lumps, masses, abscess, granulomatous reaction and lesions”. It is hard to pinpoint the exact cause of these nodules, as we can see from the results, it does not seem to be filler-type dependant. Results show that nodules are possible amongst HA, non-HA and mixed fillers, with a significant proportion (33.3%) being due to HA only filler.

As nodules were the most common adverse reaction, we decided to delve further into what nodules are and what could be their potential causes. There are various types of nodules associated with fillers we were unable to specify in the study, but it is important to note these subtypes for your own reference. ACE have categorized nodules as inflammatory delayed onset nodules (DONs) and non-inflammatory DONs and early onset nodules.25 Early onset nodules tend to be due to excessive filler placement in any one area26 or superficial placement of an incorrect filler type.

DONs typically present after weeks or months following treatment and have a variety of possible causes. Non-inflammatory DONs tend to be cool-to-touch, firm with a regular surface, likely to be caused by product misplacement or migration, in conjunction with a chronic immune-inflammatory reaction and possible low-grade bacterial infection.25 Inflammatory nodules are associated with pain, tenderness and redness, and can be contaminated with low-virulence bacteria or biofilm production.25 It is safe to assume that having a sterile treating environment is key when carrying out filler treatments, to avoid risks of contamination when penetrating the skin and depositing a foreign body in the tissues.

Product type and placement has also been proven important in preventing nodule formation. Studies have shown that noninflammatory DONs are most common with PLLA and particulate fillers.26 High G prime fillers are more likely to cause nodules if placed in areas such as lips or the tear trough region, so it is extremely important to be sure of which product can be used in what area. Recent trends have shown that certain fillers have a higher risk of causing nodule formation than others – fillers with short chains and low molecular weight are considered to be pro-inflammatory, and so it would be advisable to be aware of the filler’s specifics before treating.27 There have also been cases where a sudden systemic inflammatory event can trigger nodule formation at random, such as influenza, viral infections or trauma.26

Other complications, such as (but not limited to) migration, discoloration, and herpetic outbreaks have also been shown to be linked with filler placement in the lip area. There are no obvious trends regarding the filler type and the potential complications. Further studies are required to investigate if there is any specific correlation.

It is clear that fillers treatments do carry a variety of risks, despite them being labelled as “inert and non-immunogenic”,14 thus it becomes of utmost importance for us to truly understand the product we are working with, its properties and its associated risks, and how to manage those risks. We have to ensure that patients are adequately informed about the risks associated, and fully understand what those risks entail. Thankfully almost all possible side-effects are reversible, so, as long as the patient management is adequate, easy resolution of side effects should be possible. Many patients sign consent forms and agree to whatever they are being told without fully understanding what they are agreeing to. It is our job as the clinicians to ensure that the patient is fully informed and can understand, as best as possible, the nature of their procedure fully.

Though most of these complications can happen at random, there is plenty that can be done so as to minimize these risks. Ensuring that the correct filler is being used in the correct plane, having a full understanding of the product you are choosing to use, keeping a sterile environment, and having a comprehensive understanding of your patient’s medical history, will allow the clinician to have improved odds at avoiding complications. Lips are an extremely dynamic and sensitive area, so we have to be cautious to avoid over-injecting or using fillers with high G-prime or short molecular weight, and always make sure we are in the right plane.

We should endeavor to carry out further research into complications following dermal filler treatments, with more accurate data, such as brand of filler and subtype, exact area, and plane of product placement, use of needle or cannula, amount placed per area, etc. We should also consider outlining longitudinal studies of filler complications, so as to obtain a holistic understanding of the products we are working with. By gathering such data, we will then be able to refine and improve our techniques, improve and upgrade the products available and, above all, increase patient safety and decrease the risks associated.

References

- ISAPS. ISAPS internationals survey on aesthetic/cosmetic procedures performed in 2017. 2017.

- Keogh B, et al. Review of the Regulation of Cosmetic Interventions. Department of Health Publication; 2013.

- de Maio M. The minimal approach: an innovation in facial cosmetic procedures. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2004;28(5):295–300.

- Modarressi A, Nizet C, Lombardi T. Granulomas and nongranulomatous nodules after filler injection: Different complications require different treatments. Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive & Aesthetic Surgery. 2020;73(11):2010–2015.

- Eversole R, Tran K, Hansen D, et al. Lip augmentation dermal filler reactions, histopathologic features. Head and neck pathology. 2013;7(3):241–249.

- Yazdanparast T, Samadi A, Hasanzadeh H, et al. Assessment of the Efficacy and Safety of Hyaluronic Acid Gel Injection in the Restoration of Fullness of the Upper Lips. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2017;10(2):101–105.

- Turkmani MG, De Boulle K, Philipp-Dormston WG. Delayed hypersensitivity reaction to hyaluronic acid dermal filler following influenza-like illness. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2019;12:277–283.

- Requena L, Requena C, Christensen L, et al. Adverse reactions to injectable soft tissue fillers. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2011;64(1):1–34.

- Artzi O, Loizides C, Verner I, et al. Resistant and Recurrent Late Reaction to Hyaluronic Acid-Based Gel. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42(1):31–37.

- Alijotas-Reig J, Fernández-Figueras MT, Puig L. Inflammatory, immune-mediated adverse reactions related to soft tissue dermal fillers. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2013;43(2):241–258.

- Owosho AA, Bilodeau EA, Vu J, et al. Orofacial dermal fillers: foreign body reactions, histopathologic features, and spectrometric studies. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2014;117(5):617–625.

- Shahrabi-Farahani S, Lerman MA, Noonan V, et al. Granulomatous foreign body reaction to dermal cosmetic fillers with intraoral migration. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2014;117(1):105–110.

- Conrad K, Thiru S, Kandasamy T. Abscess Formation as a Complication of Injectable Fillers. Modern Plastic Surgery. 2015;05:14–18.

- Shahrabi Farahani S, Sexton J, Stone JD, et al. Lip nodules caused by hyaluronic acid filler injection: report of three cases. Head Neck Pathol. 2012;6(1):16–20.

- Van Dyke S, Hays GP, Caglia AE, et al. Severe Acute Local Reactions to a Hyaluronic Acid-derived Dermal Filler. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2010;3(5):32–35.

- Lucas-Herald A, Jamieson N, Roxburgh C. A case of acute pancreatitis: could this be caused by dermal filler injections? J Surg Case Rep. 2012;2012(8):5.

- Bachmann F, Erdmann R, Hartmann V, et al. Adverse reactions caused by consecutive injections of different fillers in the same facial region: risk assessment based on the results from the Injectable Filler Safety study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25(8):902–912.

- Cox SE, Adigun CG. Complications of injectable fillers and neurotoxins. Dermatol Ther. 2011;24(6):524–536.

- Bulam H, Sezgin B, Tuncer S, et al. A severe acute hypersensitivity reaction after a hyaluronic Acid with lidocaine filler injection to the lip. Arch Plast Surg. 2015;42(2):245–247.

- Lanteri A, Celestin R, Trovato M, et al. Lower lip necrosis. Eplasty. 2012;12:ic4.

- Cohen JL, Biesman BS, Dayan SH, et al. Treatment of Hyaluronic Acid Filler-Induced Impending Necrosis With Hyaluronidase: Consensus Recommendations. Aesthet Surg J. 2015;35(7):844–849.

- DeLorenzi C. Complications of injectable fillers, part I. Aesthet Surg J. 2013;33(4):561–575.

- Romagnoli M, Belmontesi M. Hyaluronic acid-based fillers: theory and practice. Clin Dermatol. 2008;26(2):123–159.

- Fagien S. Facial soft-tissue augmentation with injectable autologous and allogeneic human tissue collagen matrix (autologen and dermalogen). Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105(1):362–373; discussion 74–75.

- King M, Bassett S, Davies E, et al. Management of Delayed Onset Nodules. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2016;9(11):E1–E5.

- Graivier MH, Bass LM, Lorenc ZP, et al. Differentiating Nonpermanent Injectable Fillers: Prevention and Treatment of Filler Complications. Aesthet Surg J. 2018;38(suppl1):s29–s40.

- Baeva LF, Lyle DB, Rios M, et al. Different molecular weight hyaluronic acid effects on human macrophage interleukin 1β production. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2014;102(2):

305–314.