J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021;14(6 Suppl 1):S24–S26

J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021;14(6 Suppl 1):S24–S26

by Archana M. Sangha, MMS, PA-C

Ms. Sangha is a Fellow of the American Academy of Physician Assistants and Diplomate and Current President of the Society of Dermatology Physician Assistants. She practices general, surgical, and cosmetic dermatology in Bethesda, Maryland.

FUNDING: No funding was provided for this article.

DISCLOSURES: Ms. Sangha is a consultant for Sanofi/Regeneron, Incyte, Ortho Dermatologics, Pfizer, and Leo.

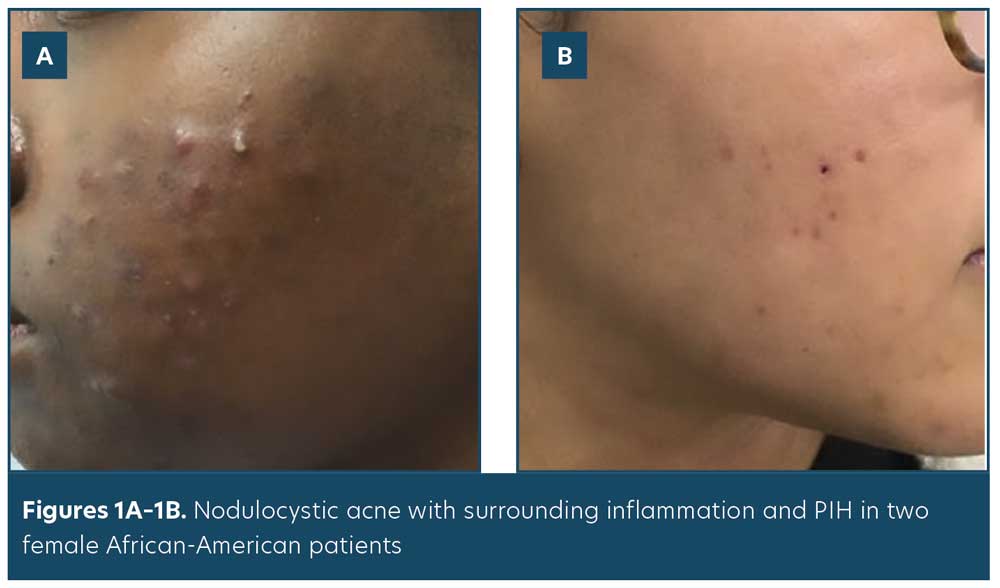

Acne is the most common skin condition in the United States, affecting over 50 million people annually.1 Skin of color (SOC) patients are more likely to develop postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH) as a result of acne. PIH is defined as an acquired hypermelanosis following cutaneous inflammation or injury of the skin.2 Nearly 50 percent of non-Caucasian women rated PIH to be “severely troublesome” in one study.3 Epidermal PIH can last for 6 to 12 months, and dermal PIH can last years.4 When surveyed, the most important acne treatment endpoint for Caucasian women was lesion clearance, whereas resolution of PIH was the most important treatment end point for non-Caucasian women.3 Addressing PIH is an important part of acne management in the SOC patient population.

Inflammation may be subclinical or difficult to observe in SOC patients; thus, it is important to treat acne early and efficaciously to minimize the sequelae of PIH and scarring. In one study, histological findings indicated that African-American women with acne had significant inflammation in all types of acne lesions; this was histologically observed, even in simple comedones, though not visible clinically. This marked increase of inflammation in SOC patients may account for the increased risk of developing PIH among this patient group (Figures 1A–B , Figure 2).5

PIH Management in SOC

Iatrogenic PIH due to irritant contact dermatitis from topical acne regimens can occur and should be avoided. It is best to choose topical products with favorable tolerability. While all retinoids are safe to use in SOC patients, it may be prudent to start at lower concentrations and titrate up as tolerated. Benzoyl peroxide (BPO) was found best tolerated when used in concentrations of 2.5 to 5.5 percent on the face, and in truncal acne, BPO concentrations up to 10 percent were found to be well tolerated when used as a cleanser or short-contact emollient foam.6 It is also imperative to counsel SOC patients on the use of gentle cleansers and non-comedogenic moisturizers, thereby further minimizing the risk of PIH due to topical products.

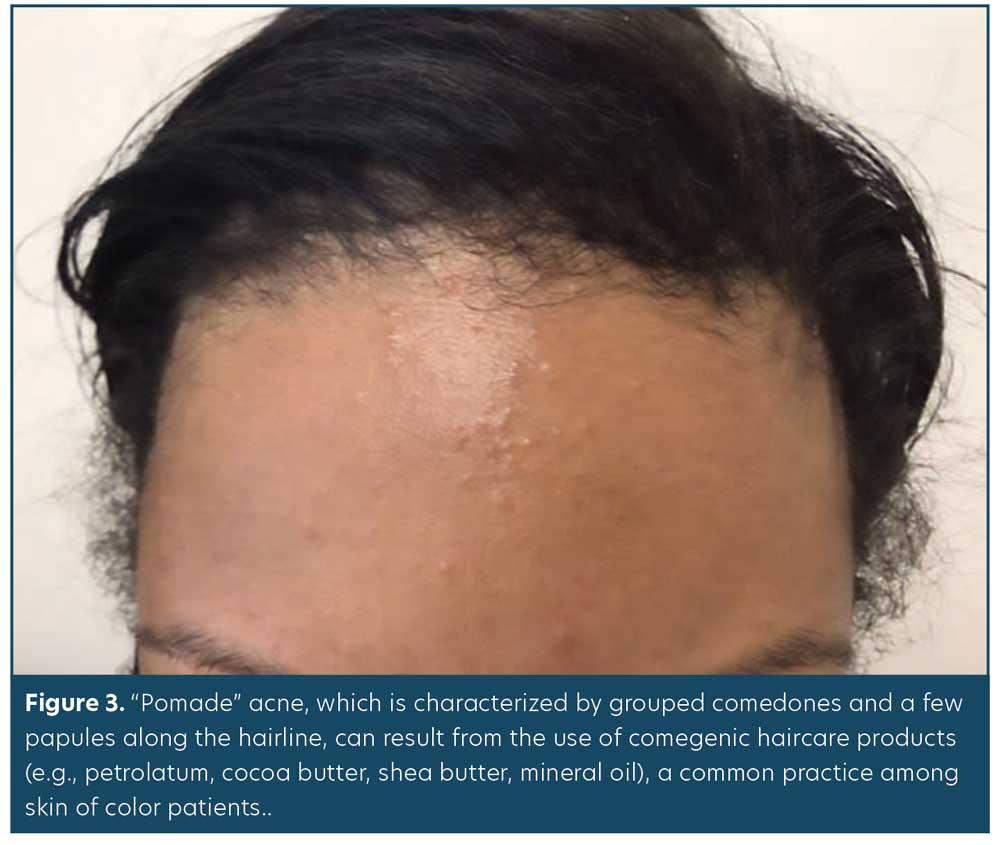

Cultural practices in SOC patients can contribute to acne and therefore PIH. Application of petrolatum, cocoa butter, shea butter, and mineral oil to the scalp, for example, is a common haircare practice in SOC populations. These comedogenic agents often lead to the development of what’s termed pomade acne, which is characterized by grouped comedones and few papules along the hairline, forehead, and temples (Figure 3). If this diagnosis is suspected, ask patients about their daily haircare practices. It’s important for patients to discontinue use of the causative product and replace with a noncomedogenic alternative.7

The most common prescription treatments for PIH include retinoids, azelaic acid, and hydroquinone. Retinoids improve PIH by modulating cell proliferation, differentiation, and cohesiveness; inducing apoptosis; and expressing anti-inflammatory properties.8 Azelaic acid (AzA) is a naturally occurring dicarboxylic acid. It has direct antityrosinase activity that has shown efficacy in the treatment of PIH. A study by Kircik9 showed that twice daily use of AzA gel 15% over 16 weeks resulted in statistically significant improvement of PIH, with over 50 percent of study participants having no PIH by the end of the study.9 Hydroquinone (HQ) is considered the gold standard for treatment of PIH. It behaves as a skin depigmenting agent by inhibiting melanin synthesis. HQ 4% once or twice daily for 3 to 6 months is often used to treat PIH. Ochronosis is a rare side effect of long-term HQ use, and is characterized by a blue-black or gray-blue discoloration; thus, it is important to educate patients on the proper use of HQ to minimize the risk of adverse effects.10 Compounded formulations with HQ have also been found to be an effective treatment for PIH.11 Specifically, a triple combination cream utilizing HQ 4%, fluocinolone acetonide 0.1%, and tretinoin 0.05% demonstrated marked efficacy and tolerability after eight weeks of treatment among patients with moderate-to-severe melasma and Fitzpatrick Skin Types I to IV (N=641).12

Daily sunscreen use is an important part of counseling SOC patients, especially those with PIH. A study by Halder et al13 found that daily use of SPF 30 or 60 for eight weeks during the summer months in African-American and Hispanic women resulted in a significant improvement of PIH. In fact, 81 percent of the patients noticed a lightening of pre-existing hyperpigmented macules, while 59 percent noted a decrease in the number of macules. Those who had applied an SPF of 60 had greater improvements in PIH than those who had applied an SPF of 30.13

Summary

In summary, PIH is associated with acne and is a common concern among SOC patients. It is important to not only address the acne in SOC patients, but to also include simultaneous management of PIH in the treatment plan. Patients should be instructed to use gentle cleansers and noncomedogenic moisturizers, avoid certain haircare products with comedogenic properties, and use sunscreen daily. Topical treatments, such as retinoids and benzoyl peroxide, should be started at lower concentrations and titrated up gradually to ensure patient tolerance. Retinoids, azelaic acid, hydroquinone, and a triple combination cream (HQ 4%, fluocinolone acetonide 0.1%, and tretinoin 0.05%) have all shown efficacy as PIH treatments. If hydroquinone is prescribed, patients should be educated on its proper use to avoid adverse effects.

References

- Bickers DR, Lim HW, Margolis D, et al. The burden of skin diseases: 2004—a joint project of the American Academy of Dermatology Association and the Society for Investigative Dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol 2006;55:490–500.

- Davis EC, Callender VD. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation: a review of the epidemiology, clinical features, and treatment options in skin of color. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2010;3(7):20–31.

- Callender VD, Alexis AF, Daniels SR, et al. Racial differences in clinical characteristics, perceptions and behaviors, and psychosocial impact of adult female acne. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:19–31.

- Zaenglein AL, Pathy AL, Schlosser BJ, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:945–973.

- Halder RM, Holmes YC, Bridgeman-Shah S, Kligman AM. A clinicohistopathologic study of acne vulgaris in black females (abstract) J Invest Dermatol. 1996;106:888.

- Alexis AF. Acne vulgaris in skin of color: understanding nuances and optimizing treatment outcomes. J Drugs Dermatol. 2014;13(6):S61–S65.

- Lawson CN, Hollinger J, Sethi S, et al. Updates in the understanding and treatments of skin and hair disorders in women of color. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2017;3(1 Suppl):S21–S37.

- Kuenzli S, Saurat JH. Retinoids. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP (eds). Dermatology, 2nd ed. Maryland Heights, MD: Elsevier Mosby; 2009.

- Kircik L. Treatment of postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and acne: a 16-week baseline controlled study. J Drugs in Dermatol. 2011;10 (6): 586.

- Schwartz C, Jan A, Zito PM. Hydroquinone. 2020 Sep 29. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan. PMID: 30969515.

- Sofen B, Prado G, Emer J. Melasma and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation: management update and expert opinion. Skin Therapy Lett. 2016 ;21(1):1–7.

- Taylor SC, Torok H, Jones T, et al. Efficacy and safety of a new triple-combination agent for the treatment of facial melasma. Cutis. 2003;72(1):67–72.

- Halder R, Rodney I, Munhutu M, Foltis P, et al. Evaluation and effectiveness of a photoprotection composition (sunscreen) on subjects of skin of color. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:AB215.