by David S. Martin, MD, FACS; HaoWei Han, MS; and Kimberly L. Farley, MSN, FNP-BC

by David S. Martin, MD, FACS; HaoWei Han, MS; and Kimberly L. Farley, MSN, FNP-BC

Dr. Martin and Ms. Farley are with Middle Tennessee Plastic Surgery in Murfreesboro, Tennessee. Mr. Han is with the Debusk School of Osteopathic Medicine, Lincoln Memorial University in Harrogate, Tennessee.

FUNDING: No funding was provided for this study.

DISCLOSURES: The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

ABSTRACT: A 25-year-old man seeking increased prominence of the cheeks self-injected a topical skin preparation containing hyaluronic acid into his malar soft tissues. Labeling and marketing of the product, which highlighted the hyaluronic acid as one of the ingredients, might have contributed to his misunderstanding of the intended use for the product. Additionally, a popular medical-based talk show and numerous videos online contributed to the errant belief that self-administration was a viable option. Complications from the injection of nonpharmaceutical substances of this type and implications for treatment in clinical practice are discussed.

KEYWORDS: Dermal fillers, complications, cosmetics, hyaluronic acid, hyaluronidase, nonmedical, self-injection, soft tissue augmentation, sunscreens, unlicensed

J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2019;12(8):51–54

Popularity of injectable dermal fillers has grown enormously in recent years, because they offer a cosmetic improvement without surgery and are associated with lower costs, shorter recovery times, and generally predictable results.1 Absorbable fillers approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) include hyaluronic acid, collagen, calcium hydroxylapatite, and poly-L-lactic acid, whereas polymethylmethacrylate is the only nonabsorbable option.2 Among these fillers, hyaluronic acid is the most widely used in Europe and the United States, with effects lasting for 6 to 18 months.1,2

According to the Cosmetic Surgery National Data Bank Statistics for 2017 from the American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery, hyaluronic acid injection is the second most common nonsurgical aesthetic procedure, after botulinum toxin injection.3 The popularity, general safety, and predictability of outcome of injectable dermal fillers are appealing to both healthcare providers and patients. However, the high cost of authentic filler materials has led to instances of improper injections by clinicians and others, including patients themselves. Injections of substandard products or of substances that are not intended for injection by nonmedical personnel can result in adverse outcomes, including abnormal pigmentation, lymphedema, infection, granulomatous reactions, necrosis, and thromboembolization.4 We report the case of a young adult man who experienced complications following the self-injection of a topical skin preparation containing hyaluronic acid into his bilateral infraorbital areas.

Case Presentation

A 25-year-old African American man with a medical history of schizophrenia presented to our plastic surgery clinic with bilateral infraorbital edema and hyperpigmentation. He reported watching a local television program demonstrating the improved appearance of an individual receiving hyaluronic acid filler injections for cheek enhancement. He then searched online for cosmetic products containing hyaluronic acid and ultimately purchased Neutrogena® “Hydra Boost water gel with sunscreen” (Johnson & Johnson, New Brunswick, New Jersey) with hyaluronic acid listed on the front label (Figure 1). This product is clearly intended for topical use and is available for purchase at a variety of retail locations and internet sites. The patient reported self-injecting his bilateral infraorbital areas with this compound approximately three months prior to seeking treatment. He obtained the syringe and needle online but could not provide any specific information regarding its size and gauge. He had not developed any infectious complications but reported firm, nodular texture, tenderness, and hyperpigmentation in the areas of injection. He also reported some mild pruritis.

He was currently receiving treatment for his schizophrenia under the supervision of a psychiatrist. He reported adhering to his antipsychotic medications and denied having auditory/visual hallucinations or altered thinking. He took no other medications, denied any drug allergies, and had no other significant medical history.

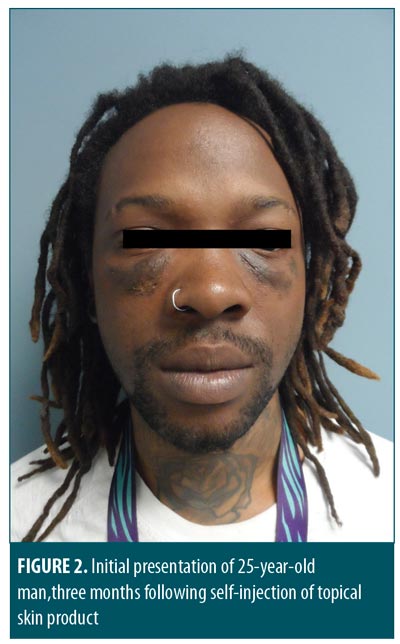

Upon physical examination of the face, firm infraorbital swelling bilaterally was observed (Figure 2). Infraorbital areas exhibited hyperpigmentation without any sinus tracts or infection. At the inferior edge of the swellings, just lateral to his alar rim, there were some small (<3mm) ulcerations with overlying dry eschar. Consistent with the injection puncture sites, four of these were noted on the right cheek and three on the left. Intraoral and ocular examination findings were unremarkable.

Listed active ingredients of the topical skin care formulation injected by the patient include avobenzone (2%), homosalate (4%), octisalate (4%), and octocrylene (2%), all of which are sunscreen compounds. The primary ingredient was glycerin, and we ultimately concluded that hyaluronic acid, though listed prominently on the front label, comprised only a small proportion of the product (presumably <2% based on named ingredients).

We contacted the manufacturer, Johnson and Johnson, seeking more detailed information about the product’s ingredients and relative concentrations. Citing proprietary and product liability concerns, their representative was reluctant to provide any additional information or recommendations to us. We then contacted the toxicologists at the Tennessee Poison Center, one of 55 facilities accredited in the United States by the American Association of Poison Control Centers and a participating site of the National Poison Database, to seek their guidance; they indicated the named contents were generally nontoxic and identified no records in their database of similar reported events.

Topical hydroquinone was initiated to treat hyperpigmentation. Additionally, although hyaluronic acid was thought to represent a small component of the substance injected, hyaluronidase 150 USP units/mL was injected into the malar nodules in 0.1 to 0.2mL increments, based on palpable firmness, for a total of 0.6mL of injected solution into the right infraorbital area and 0.4mL into the left infraorbital area. The patient was advised to continue application of the topical 4% hydroquinone cream twice daily.

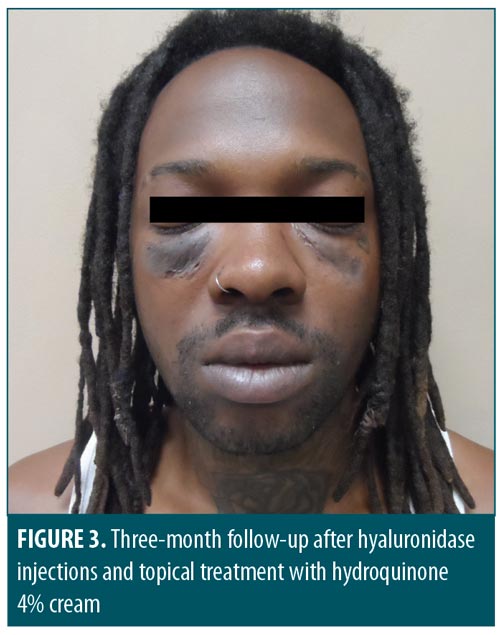

Thirty-five days after his initial hyaluronidase treatment, the patient returned for re-evaluation. Physical examination showed the original palpable infraorbital swellings had diminished in size and projection by 80 percent (Figure 3). The right medial infraorbital area exhibited some residual induration, so an additional 0.4 mL of hyaluronidase was injected. The left infraorbital area required no additional treatment. The hyperpigmentation was slightly diminished. The remainder of his physical examination remained unchanged. After three additional months of treatment, the subcutaneous induration had resolved, though hyperpigmentation persisted.

Discussion

The appeal and apparent ease of cosmetic improvement using injectable fillers has led to instances of the improper injection of a range of substances by individuals seeking improved physical appearances. Substances reported in medical journals as having been intentionally injected have included industrial silicone, petroleum jelly, paraffin, cod liver oil, beeswax, and lanolin,5 and some reports have even mentioned the injection of tire sealant and cement.6 Aggressive marketing of all forms of cosmetic products and services, the availability of substances and online injection protocols, and the high costs of approved cosmetic fillers might influence individuals to seek injection of cosmetic fillers by nonmedical personnel in nonhealthcare environments or injections of material not approved for human injection.7 Underlying psychosocial problems have also been noted to be more prevalent in the self-injection population.8

Issues regarding FDA oversight of cosmetics can be found on their website, which can be summarized as follows: the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FD&C Act) defines cosmetics as “articles intended to be rubbed, poured, sprinkled, or sprayed on; introduced into; or otherwise applied to the human body for cleansing, beautifying, promoting attractiveness, or altering the [physical] appearance.” 9,10 While cosmetic product manufacturers are not required to obtain FDA approval before selling their goods, a manufacturer is responsible for assuring safety prior to marketing. Companies can register through the Voluntary Cosmetic Registration Program to assist the FDA in gathering data and regulating the market. The FDA scrutinizes manufacturing facilities and surveys sample products to ensure their safety, and has the power to penalize any firm that violates laws pertaining to public safety. Lastly, the FDA has formally cautioned the public not to purchase injectable filler materials from online sources, to never undergo injections of unapproved fillers or liquid silicone for body contouring or enhancement, and to seek out only licensed healthcare providers in legitimate healthcare settings.11

Among the ingredients of the product injected by the present patient, glycerin is one of the most widely used substances in manufacturing and is contained in many topical preparations. It is a water-soluble, hygroscopic liquid and serves to link three carboxylic acid chains to form triglyceride. It is used in the manufacturing of a variety of products, including tobacco, paper, electronics, and cosmetics. Its contribution to topical cosmetic products arises from its hydrophilic property, which attracts and maintains water in the skin, improving texture. Glycerin is considered nontoxic to human cells when applied topically, on mucus membranes, or when ingested, and is found in lozenges, suppositories, skin preparations, and cough remedies. It has a neutral pH, though its tendency to attract water can make injection painful due to tissue engorgement.12

Countries vary in the extent and structure of regulations of topical sunscreens. In the United States, sunscreens are considered drugs and are therefore more heavily regulated by the FDA. The purpose of sunscreen is to reduce cutaneous exposure to ultraviolet radiation, ultimately reducing the risks of sunburn, skin malignancies, and other skin damage. Currently, the eight most commonly used topical sunscreens are oxybenzone, avobenzone, octinoxate, octisalate, homosalate, octocrylene, titanium dioxide, and zinc oxide.13 Topical sunscreens should be chemically inert, nonirritating, nontoxic, and otherwise safe.14 When applied topically, sunscreen ingredients are generally nontoxic and serum levels are generally low. However, sunscreen ingredients have been identified in breast milk, which raises questions of prenatal exposure.15 Sunscreen allergy and photosensitivity have been reported but make a small contribution, overall, to cosmetic product allergies as a whole, though available reports can underestimate the true incidence.16 Lastly, studies have shown that oxybenzone, a weak estrogen, has antiandrogenic effects in boys17 and might be associated with the development of endometriosis in women.18 Homosalate, a common sunscreen ingredient, has been found to be an endocrine disruptor chemical.19 Although definitive studies are lacking and clinically significant effects are likely to be rare, symptoms of hormonal changes (e.g., gynecomastia, decreased libido) are potential effects of homosalate-containing sunscreens in susceptible individuals or with excessive use generally. However, unless substantial quantities of homosalate are injected, the risk of endocrine abnormalities is small.

While injections of FDA-approved materials commonly cause minor complications, such as erythema, edema, and bruising, rare but serious complications, such as blindness, have also been reported.20 The injection of products intended for topical application only can lead to numerous additional problems due to nonsterility, having inconsistent droplet and particle size, and potential contamination by inferior ingredients. Injection of topical products into subcutaneous tissues can lead to localized infection, cellulitis, and intense tissue response, including the potential for vascular occlusion, embolization, and tissue necrosis. The pathologic immune response to these materials is typically one of nonallergic granulomatous inflammation, characterized histologically by multinucleated giant cells like those encountered in response to various types of foreign bodies.21

Conclusion

Societal emphasis on optimal physical appearance, high costs of FDA-approved filler materials, and the wide availability of online injection protocols are risk factors for an increased prevalence of attempted cosmesis through the injection of unsuitable filler materials and injection of filler material by an unqualified person. Additionally, popular terms such as “stem cell therapy” and “hyaluronic acid,” among others, are frequently attached to the labeling and marketing of noninjectable (“over-the-counter”) cosmetic products to increase their sales appeal, which can lead to confusion among the public about product contents and intended uses. Treatment of individual patients who have undergone improper cosmetic filler procedures involves careful history-taking and physical examination, investigation of product contents, and formulation of an individualized plan of treatment. In addition, mental healthcare and patient education are helpful to predict prognosis, assure patient adherence with treatment, and avoid additional episodes and complications. Data aggregation and investigation from government agencies, as well as cooperation with cosmetic product manufacturers, would also be helpful.

References

- Funt D, Pavicic T. Dermal fillers in aesthetics: an overview of adverse events and treatment approaches. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2013;6:295–316.

- United States Food and Drug Administration. Dermal fillers approved by the Center for Devices and Radiological Health. https://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/ProductsandMedicalProcedures/CosmeticDevices/WrinkleFillers/ucm227749.htm. 24 Jul 2019.

- American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery. Cosmetic surgery national data bank statistics 2017. https://surgery.org/sites/default/files/ASAPS-Stats2017.pdf. 24 Jul 2019.

- Styperek A, Bayers S, Beer M, et al. Nonmedical-grade injections of permanent fillers medical and medicolegal considerations. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6(4): 22–29.

- Haneke E. Managing complications of fillers: rare and not-so-rare. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8(4):198-210.

- Rettner R. Illegal silicone butt injections cause host of health problems. https://www.livescience.com/51275-silicone-butt-injections-health-problems.html. 24 Jul 2019.

- Park ME, Curreri A, Taylor GA, Burns K. Silicone granulomas, a growing problem?. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2016;9(5):48–51.

- Hyakuosoku H, Ono S. Complications after self-injection of hyaluronic acid and posphatidylcholine for aesthetic purposes. Aesthet Surg J. 2010;30(3):442–445.

- United States Food and Drug Administration. Cosmetics & U.S. law. https://www.fda.gov/Cosmetics/GuidanceRegulation/LawsRegulations/ucm2005209.htm. 24 Jul 2019.

- United States Food and Drug Administration. FDA authority over cosmetics: how cosmetics are not FDA-approved, but are FDA-regulated. https://www.fda.gov/Cosmetics/GuidanceRegulation/LawsRegulations/ucm074162.htm#What_kinds. 24 Jul 2019.

- United States Food and Drug Administration. The FDA warns against injectable silicone for body contouring and enhancement. https://www.fda.gov/ForConsumers/ConsumerUpdates/ucm584567.htm. 24 Jul 2019.

- The Soap and Detergent Association Glycerine & Oleochemical Division. Glycerine: an overview. http://www.aciscience.org/docs/glycerine_-_an_overview.pdf. 24 Jul 2019.

- Reisch M. After more than a decade, FDA still won’t allow new sunscreens. https://cen.acs.org/articles/93/i20/Decade-FDA-Still-Wont-Allow.html. 24 Jul 2019.

- Latha MS, Martis J, Shobha V, et al. Sunscreening agents: a review. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6(1):16–26.

- Ruszkiewicz JA, Pinkas A, Ferrer B, et al. Neurotoxic effect of active ingredients in sunscreen products: a contemporary review. Toxicol Rep. 2017;4: 245–259.

- Goossens A. Contact-allergic reactions to cosmetics. J Allergy (Cairo). 2011;2011:467071.

- Environmental Working Group. The trouble with ingredients in sunscreens. https://www.ewg.org/sunscreen/report/the-trouble-with-sunscreen-chemicals/#.WrfSOGrwaUm. 24 Jul 2019.

- Kunisue T, Chen Z, Buck Lous GM, et al. Urinary concentrations of benzophenone-type UV filters in U.S. women and their association with endometriosis. Environ Sci Technol. 2012;46(8):4624–4632.

- Urek SY, Milgin M, Halli BU. Toxicological profile of homeosalate as cosmetic ingredient. Global J Pathology and Microbiol. 2013 1:7–11.

- Townshend A. Blindness after facial injection. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2016;9(12):E5–E7.

- Lee M J, Kim Y J. Foreign body granulomas after the use of dermal fillers: pathophysiology, clinical appearance, histologic features, and treatment. Arch Plast Surg. 2015;42(2):232–239.