by Jennifer DeSimone, MD, and Meghan Beatson, BS

by Jennifer DeSimone, MD, and Meghan Beatson, BS

Dr. DeSimone is with Inova Schar Cancer Institute in Fairfax, Virginia, and the Department of Dermatology at Virginia Commonwealth University School of Medicine in Richmond, Virginia. Ms. Beatson is with the George Washington University School of Medicine in Washington, DC; the Department of Dermatology at Alpert Medical School of Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island; and the Center for Dermatoepidemiology-111D at Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Providence, Rhode Island.

FUNDING: No funding was provided for this study.

DISCLOSURES: The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

ABSTRACT: Objective. We present a successful multidisciplinary treatment approach used for a patient with rapidly developing, high-volume, and high-risk squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs), addressing short-term treatment, long-term maintenance, and appropriate preventative strategies in a difficult patient population.

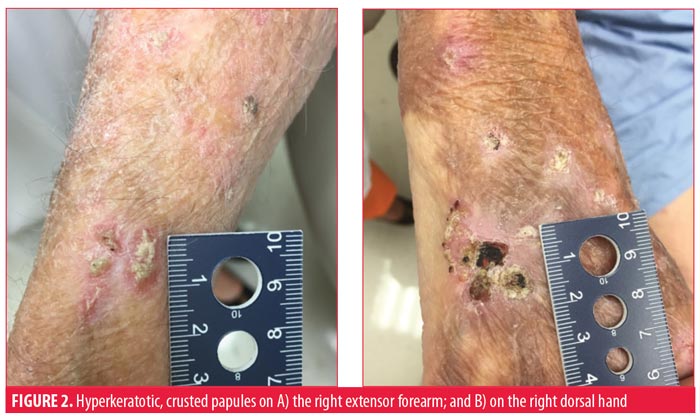

Case report. An immunocompetent, 84-year-old, Caucasian man with at least 30 SCCs of the scalp, head, neck, and upper extremities, including a 4-cm SCC on the vertex of the scalp infiltrating to the periosteum, presented to a cutaneous oncology clinic. Initial physical examination revealed nearly confluent, erythematous, hyperkeratotic, crusted papules and plaques on the head, neck, back, arms, and dorsal hands, all of which were clinically obvious SCC. Nonlesional skin displayed widespread epidermal dysplasia. The patient was seen by the clinic’s medical oncology and dermatology teams in coordinated dual visits. The invasive scalp lesion was treated by Mohs surgery and radiation, and the large SCC and field cancerization were successfully treated with a combination of topical and intralesional 5-fluorouracil with pulsed oral capecitabine, which resulted in a significant reduction in SCC disease burden.

Conclusion. Management of patients with overwhelming numbers of SCCs is extremely challenging. Combination topical and/or intralesional 5-fluorouracil and oral capecitabine may be considered as part of the management approach when mechanical destruction and surgery alone are not feasible. Multidisciplinary care coordinated between the surgeon, dermatologic oncologist, medical oncologist, and radiation oncologist is essential for providing comprehensive treatment and deploying preventative strategies in this population at high risk for metastatic SCC formation.

KEYWORDS: Carcinogens, nonmelanoma skin cancer, squamous cell carcinoma

J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2019;12(8):47–50

In cutaneous oncology, dermatologists encounter challenging patients who present with a very high number (>20) of keratinocyte carcinomas (KCs) and clinically obvious field cancerization on multiple body sites. Using traditional treatment methods to treat a patient with numerous skin lesions might not be logically feasible, especially if the patient is rapidly developing new lesions. Sequential therapeutic targeting of individual lesions in patients such as this can be unsuccessful in the long term. Furthermore, patients with numerous cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) have an increased risk of aggressive tumor behavior, with no standardized treatment algorithms currently in existence to aid clinicians in managing these difficult patients.1 We present the case of an 84-year-old man with a significant number of squamous cell carcinomas who was successfully treated with a combination of topical and intralesional 5-fluorouracil and oral capecitabine.

Case Presentation

An 84-year-old Caucasian man presented to our clinic with at least 30 SCCs of the scalp, head, neck, and upper extremities (Figures 1–3). The patient was immunocompetent and had no family history of skin cancers. He denied any blistering burns or chronic ultraviolet exposure. Of note, he was a retired Marine who fought in the Vietnam War and reported Agent Orange exposure. He developed KCs in his twenties, almost immediately upon his return from the war to the United States in the late 1960s.

The patient suffered many recurrent SCCs, despite being treated with approximately 20 prior Mohs micrographic surgeries (MMS). A 4-cm SCC on the vertex of the scalp infiltrating to the periosteum and recalcitrant to 55-Gy radiation therapy was excised with clear margins and repaired with an advancement flap. Computed tomography of the head and neck showed no metastatic disease. The high-risk scalp lesion prompted his referral to cutaneous oncology.

He presented to our skin cancer clinic with nearly confluent, erythematous, hyperkeratotic, crusted papules, plaques, and macules on the head, neck, back, arms, and dorsal hands clinically consistent with overlapping hyperkeratotic actinic keratoses, cSCCIS and invasive cSCC. The nonlesional skin also appeared abnormal and consistent with widespread epidermal dysplasia. The largest lesions were painful and bothersome to the patient, and debulking shave biopsies were performed, all of which confirmed invasive SCC.

His face, scalp, and ears were treated with topical 5-flurouracil cream 5% twice a day for 30 days. He had an excellent clinical response in the treatmed areas, with a reduction in the total number of lesions as well as in the size of individual lesions. Given the overwhelming number of thick lesions on the extremities, which were unlikely to respond to skin-directed therapy, the patient was then placed on oral capecitabine 500mg twice daily for 14 days on and seven days off to debulk the upper-extremity lesions. After three cycles, improvement was observed, including decreases in diameter, depth, and hyperkeratosis of multiple lesions while using the capecitabine. The three largest lesions were also injected with 5-flourouracil 50mg/mL, approximately 0.2ccs per lesion, repeated every three weeks for three total serial injections. After seven cycles of capecitabine, dramatic improvement was noted, with near-complete resolution of the largest lesions on the face, neck, and arms.

Discussion

Because the patient was immunocompetent with reported minimal lifetime sun exposure and no strong family history of skin cancers, his noted Agent Orange exposure while serving in Vietnam is an interesting consideration in the pathogenesis of his overwhelming KC burden. The patient’s risk factors for KC include his age, sex, skin type (Fitzpatrick Skin Type II, with fair skin and light blue eyes), and Agent Orange exposure. Recall bias is possible, and the patient might not have accurately estimated his ultraviolet light exposure, as we acknowledge that he was in an equatorial location in the 1960s (albeit for less than two years) when sunscreen was neither readily available nor routinely used. However, it should be noted that all of his lesions were located in sun-exposed areas that overlapped with chemical exposure sites.

During the Vietnam War, the United States military sprayed the herbicide, Agent Orange—a mixture of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D) and 2,4,5-trichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4,5-T)—over the rural landscape in Vietnam to prevent opposition forces from hiding in the vegetation.2 The most toxic form of dioxin, 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD), was an inadvertent contaminant present in Agent Orange.2 TCDD has been classified by the World Health Organization as a human carcinogen.3 Agent Orange exposure has been previously associated with KCs in veterans of the Vietnam War.4,5 Further research is needed to fully understand the link between Agent Orange exposure and the development of a significant number of KCs in individual patients.

Surgery is a primary therapy for localized SCCs.6 However, in severe field cancerization with nearly confluent actinic keratoses and a high density of rapidly emerging, clinically invasive lesions, surgery is not feasible. A multidisciplinary effort between Mohs surgeons, medical oncology, dermatologic oncology, and radiation oncology is required to gain control of these lesions, due to the increased risk of aggressive tumor behavior in patients with multiple cutaneous SCCs.6 Review of these high-risk cases at tumor board is useful to achieve multidisciplinary consensus on global management, due to the lack of clear, standardized definitions of the specific features of high-risk SCCs. In our case with high-risk SCCs, the patient was seen by medical oncology and dermatology in coordinated dual visits, and his case was reviewed and updated at tumor board. The invasive scalp lesion was treated by Mohs surgery and the postsurgical plan included a combination of topical and intralesional 5-fluorouracil (dermatology) with oral capecitabine (oncology), which resulted in a major reduction of the significant SCC disease burden.

While data on the efficacy of sequential intralesional 5-fluorouracil for the treatment of SCC are limited, healthcare providers might consider this option for patients in whome surgical removal is not feasible due to their significantly high number of lesions.7 Topical 5-fluorouracil is not suggested for invasive SCCs due to the lack of dermal penetration, but it has demonstrated its effectiveness as a treatment for superficial SCCs, widespread actinic keratoses, and subclinical actinic keratoses, which makes it a critical component of the treatment plan in patients who present with rapidly emerging and clinically aggressive lesions.8,9 In addition, oral capecitabine has been shown to reduce KCs in patients with large KC tumor burden, most notably in solid-organ transplant recipients.10–12 In one case series that included 10 solid-organ transplant patients treated with 500 to 1,500mg/m2 of oral capecitabine twice daily for 14 days in a 21-day treatment cycle, there was a 68.1%±29.8% reduction in SCCs/per month in those treated for 12 months and a 53.4%±43.1% reduction in SCCs per month in those treated for 24 months, highlighting the potential of capecitabine for the chemoprevention of KCs in solid-organ transplant recipients.11 Another case series treated four patients with locally advanced or regional SCC with a combination of oral capecitabine and subcutaneous interferon alpha in addition to chemotherapy for three cycles, resulting in complete remission in two patients, a partial response in one patient, and death from an unknown cause in one patient.13 While the study was small, it suggests that this combination has therapeutic potential as a treatment option for inoperable tumors.13

Another noninvasive medical management strategy for superficial or disseminated KCs is photodynamic therapy (PDT).14 PDT is a treatment option that provides ideal cosmetic outcomes while effectively treating malignant KCs. However, one systematic review demonstrated that PDT had significantly higher recurrence rates after preliminary clinical responses, compared to other treatment options.15 Furthermore, PDT is not recommended for invasive SCCs.16 One study looked at 55 patients with 112 biospy-proven lesions of Bowen’s disease and SCC treated with two sessions spaced seven days apart of methylaminolaevulinate cream application and then PDT, and followed them for 24 months.17 Complete clinical response (CR) was significantly less for patients with invasive lesions, with a 45.2 percent (14/31) CR rate at three months and a 25.8 percent (8/31) CR rate at 24 months.17 Given that the CR results were more favorable for the in-situ lesions, with a 87.8 percent (36/41) rate at three months and a 70.7 percent (29/41) rate at 24 months, PDT is arguably a valuable treatment option for superficial Bowen’s disease and SCC, but is not recommendable for invasive lesions.17 Several cellular intrinsic factors have been identified for their involvement in the development of the resistance of aggressive SCCs to PDT, further supporting that PDT should not be used in patients with invasive SCCs.18 In KCs, PDT can be combined with immunomodulatory or chemotherapeutic agents to improve its effectiveness.19 Chemotherapeutic agents that have been combined with PDT include 5-fluorouracil, diclofenac, methotrexate, and ingenol mebutate.19 The sequential application of PDT and imiquimod (5%) to treat actinic keratosis provides a better clinical and histological response than either modality alone.20 While there is no evidence for the application of this therapeutic combination in invasive SCC, topical imiquimod (5%) can be added to induce complete response and prevent tumor recurrence after PDT for both Bowen disease and BCC.21

Management of an overwhelming SCC burden has not been standardized, but the combination of topical and/or intralesional 5-fluorouracil with oral capecitabine showed an impressive clinical response in this patient. Close follow-up in a multidisciplinary dermatology-oncology clinic for periodic scheduled topical field treatments and surveillance for recurrent or new lesions are required.

Conclusion

Management of patients with a high number of KCs is challenging. Combination topical and/or intralesional 5-fluorouracil and oral capecitabine shows potential as an effective treatment option when mechanical destruction and surgery alone are not feasible. Multidisciplinary care coordinated between the Mohs surgeon, dermatologic oncologist, medical oncologist, and radiation oncologist is essential in providing comprehensive treatment and preventative strategies in this population at high risk for metastatic SCC formation. Delivery of care in a multidisciplinary cutaneous oncology clinic facilitates provider coordination, expedites multimodality treatment, and offers enhanced communication and convenience to patients.

References

- DeSimone JA, Karia PS, Schmults CD. Recognition and management of high-risk (aggressive) cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/recognition-and-management-of-high-risk-aggressive-cutaneous-squamous-cell-carcinoma. 6 Aug 2019.

- Committee to Review the Health Effects in Vietnam Veterans of Exposure to Herbicides (Tenth Biennial Update); Board on the Health of Select Populations; Institute of Medicine; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Veterans and Agent Orange: Update 2014. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US); 2016 Mar 29.

- Sorg O. AhR toxicity and dioxin toxicity. Toxicol Lett. 2014; 230(2):225–233.

- Patterson AT, Kaffenberger BH, Keller RA, Elston, DM. Skin diseases associated with Agent Orange and other organochloride exposures. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016; 74(1):143–170.

- Clemens MW, Kochuba AL, Carter ME, et al. Association between Agent Orange exposure and nonmelanotic invasive skin cancer: a pilot study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;133(2):432–437.

- Kauvar ANB, Arpey CJ, Hruza G, et al. Consensus for nonmelanoma skin cancer treatment, part II: squamous cell carcinoma, including a cost analysis of treatment methods. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41(11):1214–1240.

- Metterle L, Nelson C, Patel N. Intralesional 5-fluorouracil (FU) as a treatment for nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC): a review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016; 74(3):552–557.

- Amini S, Viera MH, Valins W, Berman B. Nonsurgical innovations in the treatment of nonmelanoma skin cancer. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2010; 3(6):20–34.

- Galiczynski EM, Vidimos AT. Nonsurgical treatment of nonmelanoma skin cancer. Dermatologic Clin. 2011; 29(2):297–309.

- Rudnick EW, Thareja S, Cherpelis B. Oral therapy for nonmelanoma skin cancer in patients with advanced disease and large tumor burden: a review of the literature with focus on a new generation of targeted therapies. Int J Dermatol. 2016; 55(3):249–258.

- Endrizzi B, Ahmed RL, Ray T, et al. Capecitabine to reduce nonmelanoma skin carcinoma burden in solid organ transplant recipients. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39(4):634–645.

- Jirakulaporn T, Mathew J, Lindgren BR, et al. Efficacy of capecitabine in secondary prevention of skin cancer in solid organ-transplanted recipients (OTR). J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(15S):1519–1519.

- Wollina U, Hansel G, Koch A, et al. Oral capecitabine plus subcutaneous interferon alpha in advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2005;131(5):300–304.

- Bhandari PR, Pai VV. Novel medical strategies combating nonmelanoma skin cancer. Indian J Dermatol. 2014; 59(6):531–546.

- Lansbury L, Bath-Hextall F, Perkins W, et al. Interventions for non-metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the skin: systematic review and pooled analysis of observational studies. BMJ. 2013;347:6153.

- Griffin LL, Lear JT. Photodynamic therapy and non-melanoma skin cancer. Cancers. 2016; 8(10):98.

- Calzavara-Pinton PG, Venturini M, Sala R, et al. Methylaminolaevulinate-based photodynamic therapy of Bowen’s disease and squamous cell carcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159(1):137–144.

- Gilaberte Y, Milla L, Salazar N, et al. Cellular intrinsic factors involved in the resistance of squamous cell carcinoma to photodynamic therapy. J Investig Dermatol. 2014;134(9): 2428–2437.

- Lucena SR, Salazar N, Gracia-Cazaña T, et al. Combined treatments with photodynamic therapy for nonmelanoma skin cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16(10):25912–25933.

- Serra-Guillen C, Nagore E, Hueso L, et al. A randomized pilot comparative study of topical methyl aminolevulinate photodynamic therapy versus imiquimod 5% versus sequential application of both therapies in immunocompetent patients with actinic keratosis: Clinical and histologic outcomes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66(4):131–137.

- Victoria-Martínez AM, Martínez-Leborans L, Ortiz-Salvador JM, Pérez-Ferriols A. Treatment of Bowen disease with photodynamic therapy and the advantages of sequential topical imiquimod. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2017;108(2):9–14.