aDavid B. Harker, MD; bJake E. Turrentine, MD; aSeemal R. Desai, MD

aDavid B. Harker, MD; bJake E. Turrentine, MD; aSeemal R. Desai, MD

aThe University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, Texas

bMedical College of Georgia at Augusta University, Augusta, Georgia

Disclosure: The authors report no relevant conflicts of interest.

Abstract

A 34-year-old woman was referred to the authors’ dermatology clinic for evaluation of right labial swelling and dyspareunia. Her symptoms began after receiving a liquid silicone injection into the buttocks at a cosmetic plastic surgery clinic that was operating illegally by an unlicensed provider. A single prior debulking surgery had produced only temporary relief of symptoms, and the swelling returned. Work-up including magnetic resonance imaging and skin biopsy revealed migration of the injected silicone from her buttock to the subcutaneous tissue of the right labia majora, with an associated granulomatous immune response to the silicone. To the authors’ knowledge, the extent of contiguous soft tissue involvement shown in this case has not yet been reported in the medical literature, nor has the finding of migration from the buttocks to the vulvar tissues to produce such dramatic asymmetry. Treatment with intralesional steroids and minocycline was initiated with improvement noted at one-month follow-up. Large volume and adulterated silicone injections are associated with a host of complications, including silicone migration and granuloma formation. No consensus for treatment exists, but attempted therapies have included surgery, local steroid injections, systemic steroids, tetracycline antibiotics, and other immune modulators. Treatment must be tailored to the individual case, considering the patient’s preferences and medical history. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2017;10(4):50–54.

A 34-year-old woman with no significant medical history presented to the authors’ dermatology clinic as a referral from her obstetrician/gynecologist (OB/GYN) for right labial swelling. The swelling began 3 to 4 years prior, following liquid silicone injections into the bilateral buttocks at an illegally operating cosmetic plastic surgery clinic. A few months following the procedure, she began experiencing right vulvar pain and gradually developed swelling of the right labia majora. The swelling was associated with mild chronic pain and dyspareunia, but review of systems was otherwise negative. Six months after the swelling developed, the patient sought surgical correction at an outside facility, where some of the swollen tissue was excised under local anesthesia. This intervention provided temporary relief from the pain and swelling, but both recurred within two weeks of the operation. After this failed measure, the patient initiated care at the authors’ institution, being initially seen by OB/GYN. Work-up included a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Figure 1 and Figure 2), which showed innumerable small T2 hyperintense nodules throughout the gluteal region with extension into and throughout the ischiorectal fossa and bilateral pelvic sidewall. Extension of these nodules was seen throughout the perineum and into the subcutaneous tissues adjacent to the right labia, with continued extension of these nodules into the right inguinal canal. The right labia was asymmetrically larger than the left, which was relatively spared of the T2 hyperintense nodular structures. Given the prior failure of an excisional procedure and the diffuse spread of the injected silicone, surgical therapy was deemed inappropriate and the patient was referred to dermatology for alternative treatment options.

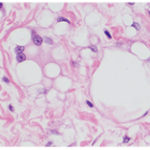

At presentation to the dermatology clinic, physical exam showed that the right labia majora was significantly enlarged compared to the left labia majora (Figure 3). The right labia exhibited pitting edema; there was subtle overlying erythema and mild warmth. Several small nodules deep in the subcutaneous tissue of the labia and buttocks could be felt, but were not easily visualized. These nodules were tender to deep compression. Punch biopsies from the right labia majora and right inferior buttocks revealed a dense granulomatous infiltrate in the dermis and subcutis (Figure 4). Histiocytes, some multinucleate, were noted to contain clear vacuolar spaces within their cytoplasm, findings consistent with silicone granulomas. No intralymphatic granulomas were seen. Laboratory work-up, including basic metabolic panel, liver function tests, complete blood count, and testing for hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) were all unremarkable. Based on the patient’s clinical presentation and objective findings, a diagnosis of metastatic silicone granulomas was made. After discussion of treatment options, the patient elected intralesional triamcinolone injections and minocycline therapy as initial treatment options. Injections were placed into the nodular areas of the right labia and right inferior buttock. The patient was also started on oral minocycline 100mg twice daily. The patient reported mild improvement after one month of therapy, and treatment with intralesional triamcinolone plus oral mincocycline was continued.

Discussion

Liquid injectable silicone has long been used as a soft tissue augmentation agent, having many innate properties that make it well-suited to this purpose. It is noncarcinogenic, minimally antigenic, can easily be sterilized, and its viscosity remains consistent across the range of temperatures experienced in the human body.1 Proper injection of pharmaceutical-grade liquid silicone using the microdroplet technique ensures that the material is appropriately encapsulated in a network of fibrous tissue, which produces superior cosmetic results and prevents substance migration.1 In contrast, large-volume injections of silicone of unknown purity are more prone to substance migration and other complications, including edema, pneumonitis, cellulitis, ulcerations, and granuloma formation.[1–6] Large-volume injections frequently have adulterants added to the silicone, which are intended to induce a more vigorous fibrotic reaction that slows substance migration.[1]

While there is a higher overall complication rate associated with large-volume impure silicone injections, a granulomatous response to silicone injection can occur with medical- and nonmedical-grade silicone injections.[7] Since silicone can migrate along tissue planes and even work its way into lymphatics, the granulomas may be found distant from the original site of injection or implantation.[1–3] The first documented occurrence of a silicone granuloma was reported in 1964, and multiple cases since then have established a granulomatous response as a recognized complication of silicone injection.[8] The granulomas can occur years after injection, and typically present as soft, fixed nodules with associated swelling and occasional overlying redness.[7] They can also present with systemic signs and symptoms, such as fever and weight loss, mimicking infection or cancer and confounding the clinical picture.[2] This is especially true when the patient seeks silicone augmentation from illegal sources or is embarrassed about receiving cosmetic medical care and is reticent to disclose the procedure to the physician on history.[2],[9]

The pathophysiology underlying silicone granuloma formation is not completely understood, although it is a subtype of foreign body granulomas.[7] Various proposed triggers of the immune response include infections, trauma, impurities in the silicone, or host proteins that adsorb to the silicone.[2],[5],[10] These factors, alone or in combination, are presumed to activate T-cells and initiate granuloma formation. More research is needed to define the exact mechanism.

Many treatment methods for silicone granulomas have been attempted, all showing varying success rates. When the disease is localized and well-circumscribed, surgical excision has been successful.[11] Intralesional steroids are also a well-recognized treatment of foreign body granulomas in general and silicone granulomas specifically.[2],[7] However, in cases of widespread disease, such as in the authors’ patient, systemic medical treatments are often required in addition to or in place of local therapies. These have included systemic steroid therapy, tetracycline antibiotics, and immunotherapies, such as tacrolimus, etanercept, and imiquimod.[2],[3],[10],[12–15] The success of tetracycline-class antibiotics is attributed to their ability to both inhibit microbial growth and suppress fibrosis through host immune system modulation.[16] There have been no large clinical trials to compare the effectiveness of the above modalities, so treatment must be considered on a case-by-case basis utilizing clinical judgment and patient preferences and considering the patient’s other medical comorbidities.

This case represents the dual challenge of both silicone migration and host granulomatous immune response, making an already difficult condition more challenging to treat. Additionally, this patient shows an extensive contiguous tissue involvement previously unreported in the literature, with the additional unique challenge of unilateral vulvar enlargement producing undesirable symptoms and cosmetic appearance. Her history makes further surgical therapies unlikely to be beneficial. Given the relative safety of tetracycline antibiotics compared to other attempted systemic modalities for this condition (steroids, biologics), it seemed most prudent to attempt a trial of local steroid injection and oral minocycline before initiating more aggressive and potentially dangerous therapeutic options.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Dr. Travis W. Vandergriff, MD, of University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center for evaluating the pathology specimens and making the histologic diagnosis.

References

1. Narins RS, Beer K. Liquid injectable silicone: a review of its history, immunology, technical considerations, complications, and potential. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;118(3 Suppl):77S–84S.

2. Lopiccolo MC, Workman BJ, Chaffins ML, Kerr HA. Silicone granulomas after soft-tissue augmentation of the buttocks: a case report and review of management. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37(5):720–725.

3. Paul S, Goyal A, Duncan LM, Smith GP. Granulomatous reaction to liquid injectable silicone for gluteal enhancement: review of management options and success of doxycycline. Dermatol Ther. 2015;28(2):98–101.

4. Altmeyer MD, Andersonn LL, Wang AR. Silicone migration and granuloma formation. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2009;8(2):92–97.

5. Schwartzfarb EM, Hametti JM, Romanelli P, Ricotti C. Foreign body granuloma formation secondary to silicone injection. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14(7):20.

6. Parikh R, Karim K, Parikh N, et al. Case report and literature review: acute pneumonitis and alveolar hemorrhage after subcutaneous injection of liquid silicone. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2008;38(4):380–385.

7. Lee JM, Kim YJ. Foreign body granulomas after the use of dermal fillers: pathophysiology, clinical appearance, histologic features, and treatment. Arch Plast Surg. 2015;42(2):232–239.

8. Winer LH, Sternberg TH, Lehman R, Ashley FL. Tissue reactions to injected silicone liquids. A report of three cases. Arch Dermatol. 1964;90:588–593.

9. Goncales ES, Almeida AS, Soares S, Oliveira DT. Silicone implant for chin augmentation mimicking a low-grade liposarcoma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2009;107(4):e21–e23.

10. Desai AM, Browning J, Rosen T. Etanercept therapy for silicone granuloma. J Drugs Dermatol. 2006;5(9):894–896.

11. Ficarra G, Mosqueda-Taylor A, Carlos R. Silicone granuloma of the facial tissues: a report of seven cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2002;94(1):65–73.

12. Crocco E, Pascini M, Suzuki N, Alves R. Minocycline for the treatment of cutaneous silicone granulomas: a case report. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2015:1–6.

13. Pasternack FR, Fox LP, Engler DE. Silicone granulomas treated with etanercept. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141(1):13–15.

14. Emer J, Roberts D, Levy L, et al. Indurated plaques and nodules on the buttocks of a young healthy female. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6(3):46–49.

15. Ellis LZ, Cohen JL, High W. Granulomatous reaction to silicone injection. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2012;5(7):44–47.

16. Tauber SC, Nau R. Immunomodulatory properties of antibiotics. Curr Mol Pharmacol. 2008;1(1):68–79.