J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2018;11(12):26–27

J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2018;11(12):26–27

by Abrahem Kazemi, MD; Olabola Awosika, MD, MS; and Cheryl Burgess, MD

Dr. Kazemi is with the Howard University College of Medicine in Washington, District of Columbia. Dr. Awosika is with the Department of Dermatology at the Henry Ford Medical Center in Detroit, Michigan. Dr. Burgess is with the Center for Dermatology and Dermatologic Surgery in Washington, District of Columbia and the Department of Dermatology at The George Washington University in Washington, District of Columbia.

Funding: No funding was provided for this study.

Disclosures: The other authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

Abstract: A 77-year-old African American woman presented to the dermatologist with two pruritic lumps in her right breast. She reported traveling to Mexico on a cruise ship two years prior to the onset of her lesions, but denied a history of previous breast masses or malignancy. Despite former radiographic evaluation by her internist revealing benign growths, and despite dermatologic treatment with intralesional steroid injections, a third new, firm nodule developed in her right breast. One such nodule eventually formed into an ulcer, and a punch biopsy revealed thin-walled vascular channels in loose inflamed stroma, coarse fibrosis, calcareous corpuscles, and an elongated parasite. Further review confirmed the parasite to be Sparganum, which is the larval stage of cestodes in the genus Spirometra. Sparganosis is a rare parasitic infection caused by the plerocercoid larva of the diphyllobothroid tapeworm. Though subcutaneous sparganosis of the breast is exceedingly rare, clinicians should consider this infection in their differential of nodular breast masses.

KEYWORDS: Subcutaneous, sparganosis, breast, nodule, skin of color, parasite, infection, Sparganum, Spirometra

Sparganosis is an uncommon parasitic infection caused by the plerocercoid larva (spargana) of the diphyllobothroid tapeworm of the genus Spirometra.1 Humans are accidental secondary hosts, and transmission is linked to consuming untreated water or partially cooked fish, or using raw meats as a topical poultice.1 The most common clinical presentation is a slow-growing, nonfluctuant or rubbery subcutaneous nodule.1,2

Case Presentation

A woman in her 70s presented with two pruritic lumps in her right breast having a six-month duration. Review of history was significant for a daily diet of seafood and travel to Mexico two years prior to the onset of her lesions. She denied previous breast masses or malignancy and household pets. Repeated evaluations by her internist, including mammography and sonography, revealed cutaneous masses in the normal right breast tissue. On examination, two firm nodules were palpated in the medial aspect of her right breast. Skin biopsy specimens revealed fibrosis of the reticular dermis with accompanying lymphohistiocytic infiltrate and increased collagen bundles, consistent with inflamed dermal scars. Subsequently, each nodule was treated twice with intralesional triamcinolone acetonide 5mg/mL (1cc) one month apart.

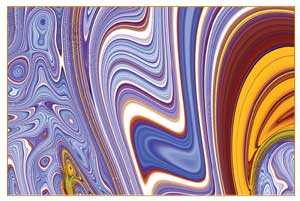

Over the following months, the patient reported no response to the intralesional steroids and developed a third itchy nodule adjacent to the original nodules in the right breast. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and lesion dehiscence occurred following treatment with diphenhydramine cream. Physical exam was significant for an ulceration overlying one of the intralesional triamcinolone acetonide treated nodules in the right breast. Punch biopsy of the ulcerated area revealed thin-walled vascular channels in loose inflamed stroma, coarse fibrosis, calcareous corpuscles, and an elongated parasite (Figure 1). Additional review confirmed the parasite to be Sparganum, the larval stage of cestodes in the genus Spirometra.

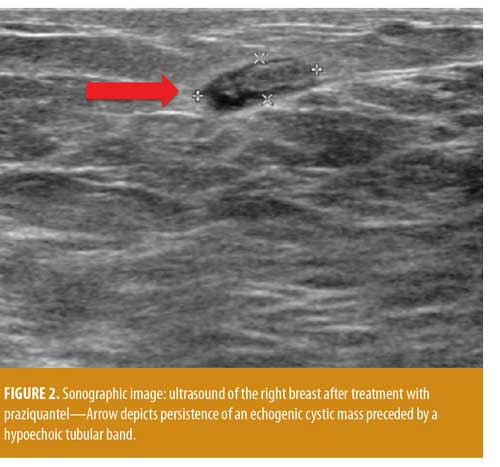

The clinical and histological diagnosis was consistent with subcutaneous sparganosis and subsequent laboratory testing was remarkable for elevated Immunogobulin E (811IU/mL). Despite following the recommended single-dose treatment with oral praziquantel 600mg, a right breast ultrasound revealed elongated, tubular, hypoechoic structures and an echogenic cystic lesion (Figure 2), consistent with persistent sparganosis. In consultation with infectious disease, the patient was recommended for surgical resection if her lesions recurred, but was lost to follow-up.

Discussion

In the United States (US), Spirometra mansonoides is the most prevalent species of spargana and human infection is extremely rare.3 Since 1882, only up to 62 cases have been reported in the US.3 The majority of cases occur in China, where the predominant species is Spirometra mansoni.2,3

Cats and dogs are the primary hosts of the adult tapeworm of the genus Spirometra. When eggs are shed in their feces, motile coracidium are released and ingested by copepods or crustaceans.4 These hosts are later consumed by fish, amphibians, or humans, allowing further development of the parasite into spargana.2,4 The cycle is completed when a primary host consumes one of these intermediate hosts, fostering maturation of the tapeworm inside their intestines. However, when human infection occurs, spargana migrate into the visceral organs or, more commonly, subcutaneous tissues.2

Subcutaneous invasion usually presents as slow-growing nodular lesions, with or without pruritus and pain from migration of the spargana.2 Histopathology demonstrates a foreign body granulomatous reaction surrounding elongated, tract-like cavities through which the spargana have traveled.1,2,5 Classically, a transverse section of the spargana will demonstrate an eosinophilic cuticle, loose stroma, and basophilic calcareous bodies.2,5 Ultrasound findings include hypoechoic tubular structures and serpiginous echogenic lesions, as seen in our patient.6 Complete surgical removal of the larva is considered curative.2,5 Antihelminthic medications, such as praziquantel, have been used with varied success.2

In this case, radiologic and dermatopathologic findings of sparganosis were crucial in making a prompt diagnosis. Though subcutaneous sparganosis of the breasts is exceedingly rare,6 clinicians should consider this infection in their differential of nodular breast masses, particularly when tubular, hypoechoic structures are present on ultrasound.

References

- Lv S, Zhang Y, Steinmann P, et al. Helminth infections of the central nervous system occurring in Southeast Asia and the Far East. Adv Parasitol. 2010;72:351–408.

- Johnson G, Gardner J, Fukai T, Goto K. Cutaneous sparganosis: a rare parasitic infection. J Cutan Pathol. 2015;42(1):1–5.

- Kim SM, Amponsah EK, Eo MY, et al. Clinical manifestation of a patient with forehead sparganosis. J Craniofac Surg. 2017;28(4): 1081–1083.

- Feigenbaum L, Motaparthi K, Fradin M. A serpiginous plaque on the trunk. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152(7):831–832.

- Griffin MP, Tompkins KJ, Ryan MT. Cutaneous sparganosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 1996;18(1): 70–72.

- Choi SJ, Park SH, Kim MJ, et al. Sparganosis of the breast and lower extremities: sonographic appearance. J Clin Ultrasound. 2014;42(7):

436–438.