J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2019;12(5):11–18

J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2019;12(5):11–18

by Heloísa Del Castanhel Ubaldo, MD; Lismary Aparecida de Forville Mesquita, MD; and Roberto Gomes Tarlé, MD, PhD

Drs. Ubaldo and Mesquita are with the Department of Dermatology at the Hospital Santa Casa de Curitiba in Paraná, Brazil. Dr. Tarlé is with Pontifical Catholic University of Paraná in Curitiba, Brazil.

Funding/disclosures. The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

Dear Editor:

The variable clinical course, the need for assertive antibiotic management, and the possibility of complications makes the diagnosis of infective endocarditis (IE) a challenge.1 The identification of initial manifestations and prompt diagnosis are paramount for better clinical outcome.

Disseminated purpura can be related to diverse clinical situations. We report an atypical case in which this rash was the main clinical sign of IE caused by Kocuria spp., bacteria rarely associated with human diseases.

Case presentation. A 59-year-old man, employed as a civil engineer, presented to our clinic after experiencing two days of progressive, purple-colored macules on the limbs. He was admitted to the hospital for 24 hours with asthenia, limb heaviness, and an isolated fever episode (102.2°F). He reported dry cough for one week, which was diagnosed as a cold and was treated with oseltamivir, sorbitol, and dipyrone. He had no history of comorbidities or continuous medications and reported no headaches, chest pain, dyspnea, abdominal pain, myalgia, or weight loss. A trip to a dengue endemic area the month prior was reported.

Case presentation. A 59-year-old man, employed as a civil engineer, presented to our clinic after experiencing two days of progressive, purple-colored macules on the limbs. He was admitted to the hospital for 24 hours with asthenia, limb heaviness, and an isolated fever episode (102.2°F). He reported dry cough for one week, which was diagnosed as a cold and was treated with oseltamivir, sorbitol, and dipyrone. He had no history of comorbidities or continuous medications and reported no headaches, chest pain, dyspnea, abdominal pain, myalgia, or weight loss. A trip to a dengue endemic area the month prior was reported.

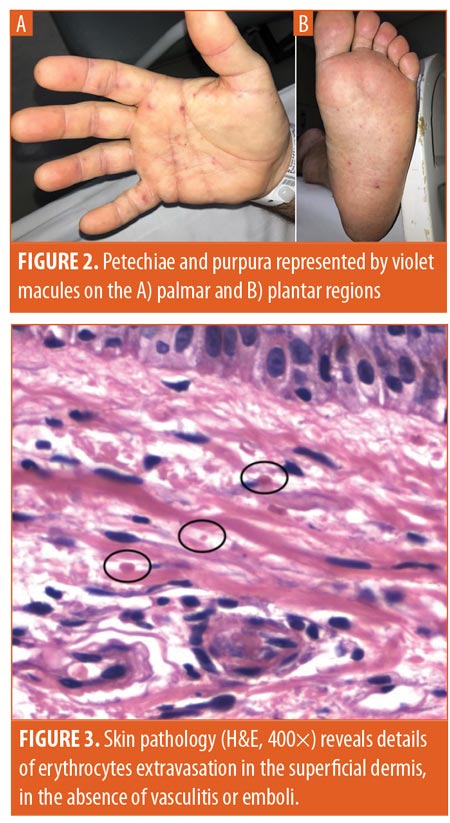

He presented in normal condition with no neurological abnormalities or altered cardiac auscultation. Dermatological evaluation revealed disseminated, nonpalpable petechiae and purpura on the trunk, limbs, and palmar and plantar regions (Figures 1 and 2). Lymphadenopathy was absent.

Laboratory work-up revealed leukocytosis (31340/mm,3 84% segmented leucocytes/4% blasts), an enlarged international normalized ratio (1.37), acute renal injury (2.5mg/dL creatinine, 126mg/dL urea), elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (21mm/h) and C-reactive protein (>450mg/dL). Negative serologies were found for syphilis, viral hepatitis, and human immunodeficiency virus. Transthoracic echocardiography was normal. The petechial rash and asthenia worsened, with sporadic febrile episodes. On the third day of hospitalization, the patient’s blood culture was positive for Gram-negative bacillus (GNB), and a transesophageal echocardiogram showed vegetations of two leaflets of the aortic valve. Subsequently, blood cultures isolated Kocuria rosea. Skin pathology demonstrated erythrocytes extravasation and absence of vasculitis or emboli (Figure 3).

The patient was diagnosed with disseminated purpura due to septic vasculopathy, secondary to IE, and was treated with ampicillin and sulbactam for 10 days, followed by four weeks of amoxicillin and clavulanate.

The patient was diagnosed with disseminated purpura due to septic vasculopathy, secondary to IE, and was treated with ampicillin and sulbactam for 10 days, followed by four weeks of amoxicillin and clavulanate.

Discussion. Kocuria rosea, a Gram-positive coccus, coagulase-negative actinobacteria that is a member of the Micrococcaceae family, is an atypical agent for endocarditis.2,3 Primarily found in soil and water,2 it is a frequent skin commensal1 and is associated with urinary tract infections, cholecystitis, peritonitis, bacteremia, arthritis, central nervous system infections, and hepatic abscesses, especially in immunocompromised patients.1–3

Approximately 15 cases of human infections by this group of bacteria have been described, with endocarditis being in the minority and lacking therapeutical guidelines.1,2 Endocarditis, however, is sensitive to most broad-spectrum antibiotics. The prevalence of Kocuria spp. infections might be underestimated considering their close similarity to coagulase-negative staphylococci.1 The growth of GNBs in culture with subsequent isolation of Kocuria spp., as in our case, has been previously reported.2 However, to our knowledge, this is the first reported case of an extensive, disseminated purpura as the initial presentation of this infection, with subsequent clinical deterioration, asthenia, and fever.

Purpura is characterized by erythrocyte extravasation to the skin or mucous membranes, presenting as violet-colored lesions not disappearing with diascopy.4 In the context of infections, purpura can be related to direct vessel invasion by the bacteria as well as to the release of bacterial toxins in the vessel wall.4 Secondary to endocarditis, typical Janeway lesions on the palms and soles result from septic embolization,4 which was not found in the patient’s anatomopathological samples. Purpura can also result from immunocomplex vasculitis, with palpable lesions, which was not evidenced in this case.4

Conclusion. This brief report emphasizes that IE diagnosis should be highly suspected in atypical infection cases, especially when associated with purpuric lesions, which can be an important dermatological sign of a life-threatening underlying disease.

References

- Gunaseelan P, Suresh G, Raghavan V, Varadarajan S. Native valve endocarditis caused by Kocuria rosea complicated by peripheral mycotic aneurysm in an elderly host. J Postgrad Med. 2017;63(2):135–137.

- Srinivasa KH, Agrawal N, Agarwal A, Manjunath CN. Dancing vegetations: Kocuria rosea endocarditis. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013: bcr2013010339.

- Garcia DC, Nascimento R, Soto V, Mendoza CE. A rare native mitral valve endocarditis successfully treated after surgical correction. BMJ Case Rep. 2014;2014: bcr2013202610.

- Criado PR. Púrpuras. In: Junior WB, Chiacchio ND, Criado PR, editors. Tratado de Dermatologia. 2nd edition. São Paulo, Brazil: Atheneu; 2014: 353–368.

- Habib G, Lanceloti P, Antunes MJ, et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of infective endocarditis: the Task Force for the Management of Infective Endocarditis of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart Journ. 2015;36(44):3075–3128.